July 21, 2005

July 18, 2005

"Power, Faith, Image": 16th-19th Century Philippine Art in Ivory:" Phillipines, Mexico, European Connections

1600-1800's: Nativity Scene, 18th century

Ecuadoran, with Hispano-Philippine ivory inserts

Bodies of wood, polychromed and gilded; faces and shoulders, ivory touched up with polychromy; (.172): H. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm); (.173): H. 8 1/2 in. (21.6 cm); (.174): L. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm)

"Power + Faith + Image: 16th-19th Century Philippine Art in Ivory" is one of the inaugural exhibits at the new Ayala Museum.

To mark the milestone exhibit, the museum organized an international symposium, "Manila, World Entrepot," on July 8-10 in which foreign and Filipino scholars read papers on the Philippine ivory trade and 19th-century Philippine watercolor images.

The Ayala Foundation published "Power Faith Image" (2004), co-authored by Regalado Trota Josè and Ramòn Villegas, a superb publication documenting the exhibition and tracing religious sculpture in ivory as an art form where the Philippines excelled globally during the Spanish colonial period.

The exhibit, curated by Josè and Villegas, is an exceptional exhibition which gathers the largest, most significant assemblage of mostly privately owned ivories, never exhibited in public. On view are 400 examples of rare Philippine ivory sculptures that establish beyond doubt the prominence of Philippine ivory sculpture in world art history.

The exhibition presents a sumptuous overview of the virtually unappreciated excellence of Philippine creativity that, while unknown to many today, of world-renowned during the Spanish colonial era.

"The Philippine ivory tradition surpassed that of any other country for its range, scope and sheer volume," write the authors. Since 1590, artisans in the Chinese district of Manila carved Christian images in ivory, prized and venerated in palaces, cathedrals, churches and monasteries in Europe and the Americas.

Christian imagery carved by Philippine craftsmen blended Oriental features along Western models. A characteristic is the expression of meditative calm in the Buddhist tradition that ranges "from an inscrutable stare to an incipient smile" articulated in all carved Philippine santos.

Eventually Philippine stylistic elements made their way into Indo-Portuguese ivories carved in Sri Lanka and India. Studies prove that "the Philippine Madonna and Child became the model for the Kuan-yin," the Chinese deity of mercy, and not the other way around as previously thought.

Evolution of forms

Basic forms evolved in ivory carving. A complete figure, whether completely of ivory or of ivory parts (usually head and hands) mounted on a fully carved wooden body, were called de bulto (origin of rebulto, Filipino for "statue").

Statues with ivory head and hands attached to an open conical framework to be covered with a dress were called de bastidor.

Some wooden statues had ivory faces that in reality were frontal masks fitted into wooden heads.

Religious scenes, called reliefs, carved into flat pieces of wood were often fitted with ivory details. Elaborate miniature tableaux of religious scenes sometimes combining ivory with glass, gold and precious stones were kept under virinas (glass covers).

Ivory was a precious object of prestige and luxury, often shown off by occupying the place of honor in a church or private home, dressed in lavishly embroidered silks and often embellished with gold, silver and precious stones.

The glory days of ivory, the exhibition implies, are of the past.

Ivory statues, now rarely seen in churches, have mostly been destroyed, vandalized or stolen. The best examples are in private collections, away from public view.

Ivory is not for the everyday. It is a ritual object. The ultimate moment of an ivory santo is when it is borne in procession. "Only when dressed in gorgeous robes... can Ivory images be seen in their best context: They are borne by believers on paths of Power, Faith and Art."

The international ivory trade was among the primary topics during the conference, which focused on linkages resulting from the exchange of objects and influences between the Philippines, Asia, Europe and the Americas during the Spanish colonial era.

Globalization

Papers read by Benito Legarda and Fernando Zialcita affirm that the galleon trade starting in 1565 that continued for most of the Spanish regime was the world's longest-running international trade route, opening a process of globalization.

Once a year, galleons plied the Manila-Acapulco route carrying products not only from the Philippines but also from all over Asia. Goods were exchanged, and so were cultural influences.

Because of the galleon trade, Zialcita said, two cultural waves met in Manila. One began in the Mediterranean, crossed the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia to the Philippines. Another wave began on the Atlantic coast of Europe, swept the opposite direction through the Americas and the Pacific toward the Philippines.

Both waves ended in the Philippines where they met other cultures, the Philippine, Chinese and the Japanese, making the Philippines "the only true end-point in the world," as Zialcita quotes French historian Pierre Chaunu.

Diverse cultures fused at the "end point" of the world. Manila festivals were so cosmopolitan that in 1611 entries to a poetry contest were submitted in Latin, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Basque, Castillian, Mexican, Tagalog and Visayan.

Philippine culture traveled to other parts of the world as well. Mangoes crossed the ocean to Mexico, where the fruit is still called mango de Manila. Vegetables cooked in coconut are called guinatan on the west coast of Mexico.

Philippine export items of prestige, however, were definitely the ivory figures venerated and honored in churches, monasteries and homes in the New World and in Spain, objects that are just beginning to capture the attention of international scholars who recognize them an important international development from the Philippines, significant in the East-West fusion of art traditions.

"Human achievements also matter," writes Zialcita.

The exhibition, publication and international conference prove that religious ivory is a human achievement of the Philippines that does matter. They are proof of Philippine excellence.

E-mail feedback to afvillalon@hotmail.com

Retratos, 2,000 years of Latin American Art

Latin America has a long and rich tradition of portraiture. For more than two thousand years, portraits have been used to preserve the memory of the deceased, provide continuity between the living and the dead, bolster the social standing of the aristocracy, mark the deeds of the mighty, record rites of passage, and, in modern times, mock the symbols of the status quo. Portraits connect the individual to the family, the family to the community, and the community to the nation. They bind together disparate populations and help establish national identity. Portraiture is an art form with which most of us identify and is an expression that provides us valuable insight into the lives and minds of the artist and sitter, as well as their time and place.

Interesting web site from the exhibition sponsored by the Ford Motor Company, curated by Marion Oettinger, Jr., interim director and curator of Latin American art at the San Antonio Museum of Art; Fatima Bercht, chief curator at El Museo del Barrio; Carolyn Carr, deputy director and chief curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery; and Miguel Bretos, a historian with expertise in Latin America and senior scholar with the National Portrait Gallery

July 12, 2005

Getty Collection:Mexico, From Empire to Revolution

Excellent site with the history, and chronology of Mexico's transistion.

...Mexico: From Empire to Revolution covers approximately sixty years. It begins in 1857 with the appointment of Benito Juárez as acting President of the Republic and the arrival of the French photographer Désiré Charnay from France. It ends with the final phases of the Revolution, the election of Álvaro Obregón as President in 1920 and the photographs of 1923 that record the bloody assassination of one of the leaders of the Revolution, Pancho Villa. This period represents one of the most dramatic and violent in Mexico’s history. In that short span of time the country experienced imperial intervention followed by conflict, rebellion and finally revolution.

There are, in a sense, two histories here, a history of Mexico and another of photography: two histories that interact and reflect upon one another. The photographs taken had a powerful influence over the course of events. Many represent photo opportunities for leaders, groups and movements to publicize themselves and their cause. Other images expose harsh realities of brutality and violence that for some are best forgotten, These images provide evidence of what had disappeared or would be otherwise lost in the folds and shadows of a larger history of a nation and countries at war....except from site.

Mexican Photography Archives

http://www.universes-in-universe.de/america/mex/photography links, excellent for research.

Postcards Of Luis Marquez, Mexican folklore and history in 20th Century Art Postcards

Great sites that explores the history of Mexican postcards, photography written by Susan Toomey Frost.

Photographer: Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

Photographer: Graciela Iturbide

Graciela finds the theatical in the ordinary, the death in the life, the history in the now. In her hands, a camera is "an instrument capable of disintigrating moral barriers, personal and social inhibitions, trusts and distrusts." A headdress of iguanas, a bull-headed bicycle, a skull mask at First Communion...Graciela conjures the dream-like from the day-to-day.

June 27, 2005

Blessing for Peace, Joy, Rain by visiting Tibetan Monks,Jewish Rabbi, Representatives of Santa Cruz

San Miguel de Allende Arts:

Sunday, June 26, 2005 at the Botanical Gardens, San Miguel de Allende, Mx

Cultivating Lovingkindness:

Permeating the Ten Directions with Loving-kindness

(1) May I be free from danger and enmity. May I be always well and happy.

(2) May my parents and teachers be always well and happy.

(3) May all beings in my home be always well and happy.

(4) May all devas in my home be always well and happy.

(5) May all beings in my village be always well and happy.

(6) May all beings in my town be always well and happy.

(7) May all beings in my country be always well and happy.

(8) May all beings in the east be always well and happy.

(9) May all beings in the south be always well and happy.

(10) May all beings in the west be always well and happy.

(11) May all beings in the north be always well and happy.

(12) May all beings in the south-east be always well and happy.

(13) May all beings in the south-west be always well and happy.

(14) May all beings in the north-west be always well and happy.

(15) May all beings in the north-east be always well and happy.

(16) May all beings in the upper direction be always well and happy.

(17) May all beings in the lower direction be always well and happy.

(From 'The Teachings of the Buddha', Ministry of Religious Affairs, Yangon, 1997)

June 21, 2005

San Miguel de Allende Arts

San Miguel de Allende Arts

Heat, Rain, Wind, better weather days in San Miguel de Allende, and San Miguel de Allende Arts continue to flourish.

Heat, Rain, Wind, better weather days in San Miguel de Allende, and San Miguel de Allende Arts continue to flourish.

June 17, 2005

June 12, 2005

San Miguel de Allende Arts

It is a hot, hot, hot, hot Sunday in San Miguel de Allende. Invocations for rains are being muttered. Cool breezes bring relief at midnight. Another dusty day tommorrow.

June 11, 2005

Patron Saint of San Miguel de Allende, Arts and Artists

San Miguel de Allende is a town known for the Arts and for Artists; and for the scent of fresh baked goods and bakeries. This is town where the sick, and the dying people come to experience a holy death and live for years; where ambulance drivers wait on the sidelines for the foolish, and during the running of the bulls everyone's foolish and runs with, around, behind, in front of the poor, frightened bulls. An appropriate Patron saint for such a small, healing town.

Name Meaning:

Who is like God? (the battle cry of the heaven forces during the uprising)

Patronage:

against temptations; ambulance drivers; ARTISTS; bakers; bankers; banking; battle; boatmen; Brecht, Belgium; Brussels, Belgium; Caltanissett, Sicily; Congregation of Saint Michael the Archangel; coopers; Cornwall, England; danger at sea; dying people; emergency medical technicians; EMTs; England; fencing; Germany; greengrocers; grocers; haberdashers; hatmakers; hatters; holy death; knights; mariners; milleners; archdiocese of Mobile, Alabama; Papua, New Guinea; paramedics; paratroopers; diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida; police officers; Puebla, Mexico; radiologists; radiotherapists; sailors; diocese of San Angelo, Texas; SAN MIGUEL DE ALLENDE, MEXICO; archdiocese of Seattle, Washington; security forces; security guards; Sibenik Croatia; sick people; soldiers; Spanish police officers; diocese of Springfield, Massachusetts; storms at sea; swordsmiths; Umbria, Italy; watermen

Prayers:

Prayer For Help Against Spiritual Enemies

Glorious Saint Michael, Prince of the heavenly hosts, who stands always ready to give assistance to the people of God; who fought with the dragon, the old serpent, and cast him out of heaven, and now valiantly defends the Church of God that the gates of hell may never prevail against her, I earnestly entreat you to assist me also, in the painful and dangerous conflict which I sustain against the same formidible foe. Be with me, O mighty Prince! that I may courageously fight and vanquish that proud spirit, whom you, by the Divine Power, gloriously overthrew, and whom our powerful King, Jesus Christ, has, in our nature, completely overcome; so having triumphed over the enemy of my salvation, I may with you and the holy angels, praise the clemency of God who, having refused mercy to the rebellious angels after their fall, has granted repentance and forgiveness to fallen man. Amen.

Representation

dragon; scales; sword

Readings:

You should be aware that the word "angel" denotes a function rather than a nature. Those holy spirits of heaven have indeed always been spirits. They can only be called angels when they deliver some message. Moreover, those who deliver messages of lesser importance are called angels; and those who proclaim messages of supreme importance are called archangels.

Whenever some act of wondrous power must be performed, Michael is sent, so that his action and his name may make it clear that no one can do what God does by his superior power.

Name Meaning:

Who is like God? (the battle cry of the heaven forces during the uprising)

Patronage:

against temptations; ambulance drivers; ARTISTS; bakers; bankers; banking; battle; boatmen; Brecht, Belgium; Brussels, Belgium; Caltanissett, Sicily; Congregation of Saint Michael the Archangel; coopers; Cornwall, England; danger at sea; dying people; emergency medical technicians; EMTs; England; fencing; Germany; greengrocers; grocers; haberdashers; hatmakers; hatters; holy death; knights; mariners; milleners; archdiocese of Mobile, Alabama; Papua, New Guinea; paramedics; paratroopers; diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida; police officers; Puebla, Mexico; radiologists; radiotherapists; sailors; diocese of San Angelo, Texas; SAN MIGUEL DE ALLENDE, MEXICO; archdiocese of Seattle, Washington; security forces; security guards; Sibenik Croatia; sick people; soldiers; Spanish police officers; diocese of Springfield, Massachusetts; storms at sea; swordsmiths; Umbria, Italy; watermen

Prayers:

Prayer For Help Against Spiritual Enemies

Glorious Saint Michael, Prince of the heavenly hosts, who stands always ready to give assistance to the people of God; who fought with the dragon, the old serpent, and cast him out of heaven, and now valiantly defends the Church of God that the gates of hell may never prevail against her, I earnestly entreat you to assist me also, in the painful and dangerous conflict which I sustain against the same formidible foe. Be with me, O mighty Prince! that I may courageously fight and vanquish that proud spirit, whom you, by the Divine Power, gloriously overthrew, and whom our powerful King, Jesus Christ, has, in our nature, completely overcome; so having triumphed over the enemy of my salvation, I may with you and the holy angels, praise the clemency of God who, having refused mercy to the rebellious angels after their fall, has granted repentance and forgiveness to fallen man. Amen.

Representation

dragon; scales; sword

Readings:

You should be aware that the word "angel" denotes a function rather than a nature. Those holy spirits of heaven have indeed always been spirits. They can only be called angels when they deliver some message. Moreover, those who deliver messages of lesser importance are called angels; and those who proclaim messages of supreme importance are called archangels.

Whenever some act of wondrous power must be performed, Michael is sent, so that his action and his name may make it clear that no one can do what God does by his superior power.

Nation Divided,By Carmen Duarte, ARIZONA DAILY STAR

An article about those trapped in between.

...A delegation of Tohono O'odham left for Washington, D.C., on June 2 to seek U.S. citizenship for 8,400 tribal members.

Tribal officials want the U.S. government to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 to make all enrolled tribal members U.S. citizens. Under the amended act, the tribal membership card would serve as proof of citizenship or a birth certificate.

"The federal government needs to right a wrong committed in 1853, when our traditional lands were divided between Mexico and the United States," Tribal Vice Chairman Henry Ramon said.

American Indians who live along the U.S.-Canadian border were given dual citizenship through treaties hundreds of years ago and have not faced separation from their people. They travel freely between both countries.

This was not done for the Tohono O'odham, Ramon said. "I am very confident that the politicians will listen to us and make it right."

The border, tribal officials say, is causing hardship for 8,400 members on both sides of it - most of them with no birth certificates to prove citizenship. The tribe has 24,000 enrolled members.

It's an ongoing problem that began intensifying in 1986 with changes in U.S. immigration laws and with beefed-up drug enforcement along 75 miles of Tohono O'odham land that abuts the border in remote desert.

For decades, with the blessing of the U.S. government, Tohono O'odham members in both countries were allowed to cross the border freely to work, participate in religious ceremonies, keep medical appointments in Sells and visit relatives.

As the border crossings became more difficult, families stopped making their routine trips. For some, health or family emergencies were worth the risk of dealing with U.S. Border Patrol agents, jail time and the confiscation of their vehicles.

In 1999, a pilot program between Mexico and U.S. immigration officials led to Mexican passports and U.S. border-crossing cards for 100 enrolled tribal members in Mexico.

That led the tribe's Legislative Council last year to allocate $102,310 to pay for the remaining 1,238 Mexican passports and U.S. border-crossing cards for Tohono O'odham in Mexico.

Immigration officials on both sides of the border worked together to make this happen -waiving certain documents, and using tribal rolls to meet requirements.

But this did not solve the problems in three situations: O'odham living in the United States who are Mexican-born; O'odham born in the United States who cannot prove it; and O'odham children who qualify for dual citizenship but don't have it.

"I am very confident that the politicians will listen to us and make it right," Ramon says.

"I think something needs to be done, but I think it will be a difficult road," said Pastor, adding that some politicians think U.S. immigration laws are already too lax.

"I will work with them to try to help them achieve their goal," Pastor said.

For centuries, said Ramon, Tohono O'odham, which means "desert people," lived on their traditional lands - lands that stretched from Phoenix south to Hermosillo, Sonora, and west to the Gulf of California.

The Tohono O'odham Nation's capital is Sells, which is about 60 miles west of Tucson. The reservation is about the size of Connecticut and includes 11 districts.

The Tohono O'odham lived there long before it was part of New Spain, and later, Mexico, after its independence was won in 1821.

The Gila River was the boundary between Mexico and the United States in 1848, when Mexico ceded the land north of it.

The river remained the international boundary until Congress ratified the Gadsden Purchase of the southern portions of New Mexico and Arizona in 1854.

Affected tribal members

The four groups of Tohono O'odham affected by the U.S.-Mexico border and laws that define nationality are:

* About 7,000 members who were born in the United States, but who do not have documents to obtain birth certificates.

Some of these people cannot get Social Security numbers, retirement benefits, veterans' benefits, widows' benefits, a driver's license or a passport.

* About 1,400 members who were born in Mexico and still live there.

* Members born in Mexico who now live illegally in the United States. Several hundred of this group are included in the tally of 7,000 affected members.

* Members born in Mexico of parents who are U.S. citizens, but whose parents cannot prove it. These members live illegally in the United States but qualify for dual citizenship. This number also is included in the 7,000 affected members.

Politicians did not take the Tohono O'odham into consideration when lines were drawn in 1853, dividing the tribe's traditional lands, said Ramon, 66, who was born in the Hickiwan District, where he grew up farming. He later became an auto mechanic, served in the Korean War, studied at the University of Utah, worked as an alcoholism counselor and entered politics in 1972.

He said the Tohono O'odham should have been guaranteed U.S. citizenship when their lands were cut in half, such as what happened with American Indians who live along the U.S.-Canadian border.

Ramon said another historical oversight in extending citizenship to members occurred in 1937, when Congress formally recognized the Tohono O'odham Nation as an indigenous sovereign government. It was then the U.S. government took a census on both sides of the border and enrolled members based on O'odham blood, not on country of residency, birth or citizenship. This census was the basis for tribal recognition.

Ramon and 66-year-old Maria Jesus Romo-Robles, an enrolled member who was born in and lives in Sonoyta, Sonora, are among the delegation's members, who will share stories with Capitol Hill politicians.

Romo-Robles and Ramon remember as children an open border with families crossing freely - no visas or birth certificates required.

Ramon remembers as a young boy stories about federal U.S. buses traveling into Mexico and picking up and bringing O'odham children to schools in Arizona.

"My father used to cross and work as a laborer at the mine in Ajo," said Romo-Robles. "He also was a vendor and would bring and sell fruit, cheese and wine to families."

Today, Romo-Robles has seven children - all tribal members - living in Eloy and the Phoenix area, working in construction, agriculture, a clothing factory and a restaurant.

One son works for the tribe in the San Lucy District, where he irrigates cotton, melon and wheat fields.

They are all living in the United States illegally. For years, Romo-Robles could not cross and see her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren because she feared prosecution.

When she was sick with gallbladder and bladder disease, she crossed through an opening in the barbed-wire fence to go to the Sells hospital.

Romo-Robles spent many holidays alone, because her children moved north for a better life.

"They say this land is ours, but they don't treat us like it is ours," she said.

"I want Congress to help my people," said Romo-Robles who left for the federal capital last week - a first in leaving her traditional O'odham lands.

"I'm ready to stand up for my nation and my children. They are my treasures. I love them dearly," she said.

* Contact Carmen Duarte at 573-4195 or at cduarte@azstarnet.com.

To contact your congressman: You can contact your congressman or senator to voice your opinion on the issue at the following numbers:

* Sen. John McCain (Republican) at (202) 224-2235 or 670-6334

* Sen. Jon Kyl (R) at (202) 224-4521 or 575-8633

* Rep. Jim Kolbe (R) at (202) 225-2542 or 881-3588

* Rep. Ed Pastor (Democrat) at (202) 225-4065 or 624-9986

...A delegation of Tohono O'odham left for Washington, D.C., on June 2 to seek U.S. citizenship for 8,400 tribal members.

Tribal officials want the U.S. government to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 to make all enrolled tribal members U.S. citizens. Under the amended act, the tribal membership card would serve as proof of citizenship or a birth certificate.

"The federal government needs to right a wrong committed in 1853, when our traditional lands were divided between Mexico and the United States," Tribal Vice Chairman Henry Ramon said.

American Indians who live along the U.S.-Canadian border were given dual citizenship through treaties hundreds of years ago and have not faced separation from their people. They travel freely between both countries.

This was not done for the Tohono O'odham, Ramon said. "I am very confident that the politicians will listen to us and make it right."

The border, tribal officials say, is causing hardship for 8,400 members on both sides of it - most of them with no birth certificates to prove citizenship. The tribe has 24,000 enrolled members.

It's an ongoing problem that began intensifying in 1986 with changes in U.S. immigration laws and with beefed-up drug enforcement along 75 miles of Tohono O'odham land that abuts the border in remote desert.

For decades, with the blessing of the U.S. government, Tohono O'odham members in both countries were allowed to cross the border freely to work, participate in religious ceremonies, keep medical appointments in Sells and visit relatives.

As the border crossings became more difficult, families stopped making their routine trips. For some, health or family emergencies were worth the risk of dealing with U.S. Border Patrol agents, jail time and the confiscation of their vehicles.

In 1999, a pilot program between Mexico and U.S. immigration officials led to Mexican passports and U.S. border-crossing cards for 100 enrolled tribal members in Mexico.

That led the tribe's Legislative Council last year to allocate $102,310 to pay for the remaining 1,238 Mexican passports and U.S. border-crossing cards for Tohono O'odham in Mexico.

Immigration officials on both sides of the border worked together to make this happen -waiving certain documents, and using tribal rolls to meet requirements.

But this did not solve the problems in three situations: O'odham living in the United States who are Mexican-born; O'odham born in the United States who cannot prove it; and O'odham children who qualify for dual citizenship but don't have it.

"I am very confident that the politicians will listen to us and make it right," Ramon says.

"I think something needs to be done, but I think it will be a difficult road," said Pastor, adding that some politicians think U.S. immigration laws are already too lax.

"I will work with them to try to help them achieve their goal," Pastor said.

For centuries, said Ramon, Tohono O'odham, which means "desert people," lived on their traditional lands - lands that stretched from Phoenix south to Hermosillo, Sonora, and west to the Gulf of California.

The Tohono O'odham Nation's capital is Sells, which is about 60 miles west of Tucson. The reservation is about the size of Connecticut and includes 11 districts.

The Tohono O'odham lived there long before it was part of New Spain, and later, Mexico, after its independence was won in 1821.

The Gila River was the boundary between Mexico and the United States in 1848, when Mexico ceded the land north of it.

The river remained the international boundary until Congress ratified the Gadsden Purchase of the southern portions of New Mexico and Arizona in 1854.

Affected tribal members

The four groups of Tohono O'odham affected by the U.S.-Mexico border and laws that define nationality are:

* About 7,000 members who were born in the United States, but who do not have documents to obtain birth certificates.

Some of these people cannot get Social Security numbers, retirement benefits, veterans' benefits, widows' benefits, a driver's license or a passport.

* About 1,400 members who were born in Mexico and still live there.

* Members born in Mexico who now live illegally in the United States. Several hundred of this group are included in the tally of 7,000 affected members.

* Members born in Mexico of parents who are U.S. citizens, but whose parents cannot prove it. These members live illegally in the United States but qualify for dual citizenship. This number also is included in the 7,000 affected members.

Politicians did not take the Tohono O'odham into consideration when lines were drawn in 1853, dividing the tribe's traditional lands, said Ramon, 66, who was born in the Hickiwan District, where he grew up farming. He later became an auto mechanic, served in the Korean War, studied at the University of Utah, worked as an alcoholism counselor and entered politics in 1972.

He said the Tohono O'odham should have been guaranteed U.S. citizenship when their lands were cut in half, such as what happened with American Indians who live along the U.S.-Canadian border.

Ramon said another historical oversight in extending citizenship to members occurred in 1937, when Congress formally recognized the Tohono O'odham Nation as an indigenous sovereign government. It was then the U.S. government took a census on both sides of the border and enrolled members based on O'odham blood, not on country of residency, birth or citizenship. This census was the basis for tribal recognition.

Ramon and 66-year-old Maria Jesus Romo-Robles, an enrolled member who was born in and lives in Sonoyta, Sonora, are among the delegation's members, who will share stories with Capitol Hill politicians.

Romo-Robles and Ramon remember as children an open border with families crossing freely - no visas or birth certificates required.

Ramon remembers as a young boy stories about federal U.S. buses traveling into Mexico and picking up and bringing O'odham children to schools in Arizona.

"My father used to cross and work as a laborer at the mine in Ajo," said Romo-Robles. "He also was a vendor and would bring and sell fruit, cheese and wine to families."

Today, Romo-Robles has seven children - all tribal members - living in Eloy and the Phoenix area, working in construction, agriculture, a clothing factory and a restaurant.

One son works for the tribe in the San Lucy District, where he irrigates cotton, melon and wheat fields.

They are all living in the United States illegally. For years, Romo-Robles could not cross and see her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren because she feared prosecution.

When she was sick with gallbladder and bladder disease, she crossed through an opening in the barbed-wire fence to go to the Sells hospital.

Romo-Robles spent many holidays alone, because her children moved north for a better life.

"They say this land is ours, but they don't treat us like it is ours," she said.

"I want Congress to help my people," said Romo-Robles who left for the federal capital last week - a first in leaving her traditional O'odham lands.

"I'm ready to stand up for my nation and my children. They are my treasures. I love them dearly," she said.

* Contact Carmen Duarte at 573-4195 or at cduarte@azstarnet.com.

To contact your congressman: You can contact your congressman or senator to voice your opinion on the issue at the following numbers:

* Sen. John McCain (Republican) at (202) 224-2235 or 670-6334

* Sen. Jon Kyl (R) at (202) 224-4521 or 575-8633

* Rep. Jim Kolbe (R) at (202) 225-2542 or 881-3588

* Rep. Ed Pastor (Democrat) at (202) 225-4065 or 624-9986

The Border

While art prices soar and Mexican Art make a prescence on the international art scsene, thousands and thousands are being shot, murdered along the US and American Borders.

For more articles, highlight the Title link.

For more articles, highlight the Title link.

Riding high on a Mexican wave,

As Tate Modern stages its major Frida Kahlo exhibition, Louise Baring reports on the resurgence of interest in art from Mexico

It was Madonna who helped transform Frida Kahlo into a collector's darling. Inspired by Frida - Hayden Herrera's bestselling 1983 biography of the Mexican painter - the singer hoped to play her in a film. Hollywood turned down the project. Mexican actress Salma Hayek took up the role in 2002, but Madonna meanwhile snapped up a couple of Kahlo paintings - including Self Portrait with Monkey, 1940 (now a key loan to the new Frida Kahlo show at Tate Modern), which she bought for more than $1 million from a Venezuelan collector who had paid just $44,000 for the picture at Sotheby's in New York in 1979. Just over a decade later, Self Portrait, 1929, sold for $5.4 million at Sotheby's in New York.

Moses or Nuclear Sun by Frida Kahlo

Kahlo's prices are "roaring upward", as one Manhattan collector puts it, in part because her work rarely comes on the market. The painter's output was small - roughly 200 works, around 50 of which cannot leave Mexico as they are regarded as national heritage. "Kahlo was also self-taught, so few of her early works are interesting," says New York-based Mexican art dealer Mary-Anne Martin. "Her late works are frequently choppy and crudely painted, as she was in tremendous pain and impaired by alcohol and painkillers."

Needless to say, forgeries are rife - though easily spotted. "At one point I was being offered one fake Frida a month," says Martin, who also has more fakes by Diego Rivera (Kahlo's husband, famous for his blend of folk art and propaganda) in her files than real ones.

The growing Latino presence in the US, combined with a slew in recent years of museum shows from ancient Mayan heads to modern video installations, has done much to revive interest in the rich artistic tradition of Mexico. As Fatima Bercht, chief curator of El Museo del Barrio in Manhattan, explains: "Mexico devotes far more resources than any other Latin American country to promoting its culture in the US."

While rich collectors such as film producer Joel Silver, former HBO boss Michael Fuchs, and Daniel Filipacchi, the chairman of Hachette, favour 20th-century Mexican masters, a younger generation of collectors - mostly Latin Americans, Americans and a sprinkling of Europeans - buy work by a new generation of Mexican artists breaking new ground: Santiago Sierra,with his sound installations;

Gabriel Orozco,(shown at the Serpentine Gallery in London last year), a popular photographer who also works in sculpture, drawing and video; Nahum B Zenil,known for his self-portraits examining his conflicting identities as a Catholic, an Indian and a homosexual; and Elena Climent,who records the lives of ordinary Mexicans in intimate still-lifes. An older photographer, 71-year-old Enrique Metinides, is recognised for his images of car crashes, bus accidents and train derailments composed like a scene from a crime or action movie.

"Unlike Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera, these Mexican artists think of themselves as international. Many have strong links with the US or Europe," says Virgilio Garza, who runs Christie's Latin American department in New York. "Gabriel Orozco, for example, is represented by the Marian Goodman gallery in New York, rather than a gallery specialising in Latin American art."

As vintage photography enjoys a golden age, photography collectors and museums chase after vintage examples by 20th-century Mexican photographic masters such as Agustin Victor Casasola, (the subject of a current retrospective at the Museo del Barrio), who documented the upheaval of the Mexican revolution along with the jazz cafés and firing squads. Manuel Alvarez Bravo,who died three years ago aged 100, combined a profoundly Mexican subject-matter with avant-garde influences; while Italian-born Tina Modotti, who modelled for both Diego Rivera and Edward Weston, is famous for her still-lifes and photographs of Mexico's working class.

Tina Modotti's Telegraph Wires

Vintage prints of Modotti's best-known images, such as Telephone Wires or Calla Lilies, now fetch up to $350,000, says Spencer Throckmorton, a New York specialist in Mexican photography. "It's hard to believe that 25 years ago, the Latin American - let alone Mexican - art market didn't really exist," says Mary-Anne Martin, who set up Sotheby's first Latin American sale in 1979, where nervous bidders sat in clusters, country by country. Enlivened by a spattering of work by Mexican stars such as Diego Rivera and Rufino Tamayo or Wilfredo Lam, a Cuban painter, and Chilean Roberto Matta, most of the lots - 40 per cent of which were bought by visiting Mexicans - had never come up at auction before.

Of course, "international" artists such as Tamayo (who deliberately avoided being represented by a Mexican gallery) or David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rivera - all of whom had painted murals in America during the 1930s - had a market. But most Mexican art languished for decades. Even Kahlo was dismissed as a local amateur, while English-language books on Mexican art could be found only in secondhand book stores.

Back in the 1930s and 1940s - a period of artistic interchange between the US and Mexico - Hollywood stars such as Edward G Robinson, Merle Oberon and Dolores del Rio snapped up Mexican art. In 1938, Edward G Robinson bought four Kahlos for $200 each - the 31-year-old painter's first major sale - while other enthusiasts included Edgar J Kaufmann, an industrialist, and Jacques Gelman, a European-born film producer who, with his wife Natasha, amassed a collection of 20th-century Mexican art.

Artistic taste changed, however, in the 1950s, when the Cold War led collectors to turn away from work that promoted socialist values. John D Rockefeller ordered workers to smash Diego Rivera's Man at the Crossroads - painted for the Rockefeller Centre in New York - when the artist refused to remove a portrait of Lenin. Kahlo's political hero, meanwhile, was Stalin. But, more importantly, the rise of post-war abstract expressionists such as Mark Rothko and Franz Kline (whose Crow Dancer fetched $6.4 million at Christie's post-war and contemporary art sale in New York last month) made the magic surrealism of Mexican art seem old-fashioned.

"I think that in the perverse way that market psychology operates, people began to respect the Mexican market once more when Frida Kahlo's prices started to climb," says Martin. The Tree of Hope, the first Kahlo to be sold at Sotheby's, in the late 1970s, did not even reach its lower estimate of $20,000. But the swell of public interest in Kahlo - a mythic creature of her own creation - combined with the introduction of Latin American sales in New York revived interest in Mexico's rich artistic tradition.

In 1990, Kahlo's Diego and I (1949), featuring a weeping Kahlo with Diego Rivera's image in her forehead, became the first Latin American painting to sell for more than $1 million. Charles Saatchi promptly asked a dealer to find him 10 or 12 self-portraits, but backed off when faced with a $3 million price tag for a self-portrait from 1940.

No Frida Kahlos were up for sale at last month's bi-annual Latin American auctions in New York, which also included 18th- and 19th-century colonial paintings. Sotheby's had a couple of important Riveras, once of which - La ofrenda (1928) - sold for $1.6 million. But while modern Mexican masters such as Maria Izquierdo, 64-year-old Francisco Toledo (the subject of a retrospective at the Whitechapel in 2000) and Gunther Gerzso can reach up to $500,000, only the colourful, textured paintings by Rufino Tamayo, who died in 1991, have sold for over $2 million,

Kahlo, meanwhile, remains by far the most expensive Mexican artist - indeed, the dearest in the whole of Latin America. Recognised even by those with scant interest in art, her work gives a collector instant status. And as Thomas Hoving, an ex-director of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, famously said: "Art is money-sexy-social-climbing fantastic."

It was Madonna who helped transform Frida Kahlo into a collector's darling. Inspired by Frida - Hayden Herrera's bestselling 1983 biography of the Mexican painter - the singer hoped to play her in a film. Hollywood turned down the project. Mexican actress Salma Hayek took up the role in 2002, but Madonna meanwhile snapped up a couple of Kahlo paintings - including Self Portrait with Monkey, 1940 (now a key loan to the new Frida Kahlo show at Tate Modern), which she bought for more than $1 million from a Venezuelan collector who had paid just $44,000 for the picture at Sotheby's in New York in 1979. Just over a decade later, Self Portrait, 1929, sold for $5.4 million at Sotheby's in New York.

Moses or Nuclear Sun by Frida Kahlo

Kahlo's prices are "roaring upward", as one Manhattan collector puts it, in part because her work rarely comes on the market. The painter's output was small - roughly 200 works, around 50 of which cannot leave Mexico as they are regarded as national heritage. "Kahlo was also self-taught, so few of her early works are interesting," says New York-based Mexican art dealer Mary-Anne Martin. "Her late works are frequently choppy and crudely painted, as she was in tremendous pain and impaired by alcohol and painkillers."

Needless to say, forgeries are rife - though easily spotted. "At one point I was being offered one fake Frida a month," says Martin, who also has more fakes by Diego Rivera (Kahlo's husband, famous for his blend of folk art and propaganda) in her files than real ones.

The growing Latino presence in the US, combined with a slew in recent years of museum shows from ancient Mayan heads to modern video installations, has done much to revive interest in the rich artistic tradition of Mexico. As Fatima Bercht, chief curator of El Museo del Barrio in Manhattan, explains: "Mexico devotes far more resources than any other Latin American country to promoting its culture in the US."

While rich collectors such as film producer Joel Silver, former HBO boss Michael Fuchs, and Daniel Filipacchi, the chairman of Hachette, favour 20th-century Mexican masters, a younger generation of collectors - mostly Latin Americans, Americans and a sprinkling of Europeans - buy work by a new generation of Mexican artists breaking new ground: Santiago Sierra,with his sound installations;

Gabriel Orozco,(shown at the Serpentine Gallery in London last year), a popular photographer who also works in sculpture, drawing and video; Nahum B Zenil,known for his self-portraits examining his conflicting identities as a Catholic, an Indian and a homosexual; and Elena Climent,who records the lives of ordinary Mexicans in intimate still-lifes. An older photographer, 71-year-old Enrique Metinides, is recognised for his images of car crashes, bus accidents and train derailments composed like a scene from a crime or action movie.

"Unlike Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera, these Mexican artists think of themselves as international. Many have strong links with the US or Europe," says Virgilio Garza, who runs Christie's Latin American department in New York. "Gabriel Orozco, for example, is represented by the Marian Goodman gallery in New York, rather than a gallery specialising in Latin American art."

As vintage photography enjoys a golden age, photography collectors and museums chase after vintage examples by 20th-century Mexican photographic masters such as Agustin Victor Casasola, (the subject of a current retrospective at the Museo del Barrio), who documented the upheaval of the Mexican revolution along with the jazz cafés and firing squads. Manuel Alvarez Bravo,who died three years ago aged 100, combined a profoundly Mexican subject-matter with avant-garde influences; while Italian-born Tina Modotti, who modelled for both Diego Rivera and Edward Weston, is famous for her still-lifes and photographs of Mexico's working class.

Tina Modotti's Telegraph Wires

Vintage prints of Modotti's best-known images, such as Telephone Wires or Calla Lilies, now fetch up to $350,000, says Spencer Throckmorton, a New York specialist in Mexican photography. "It's hard to believe that 25 years ago, the Latin American - let alone Mexican - art market didn't really exist," says Mary-Anne Martin, who set up Sotheby's first Latin American sale in 1979, where nervous bidders sat in clusters, country by country. Enlivened by a spattering of work by Mexican stars such as Diego Rivera and Rufino Tamayo or Wilfredo Lam, a Cuban painter, and Chilean Roberto Matta, most of the lots - 40 per cent of which were bought by visiting Mexicans - had never come up at auction before.

Of course, "international" artists such as Tamayo (who deliberately avoided being represented by a Mexican gallery) or David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rivera - all of whom had painted murals in America during the 1930s - had a market. But most Mexican art languished for decades. Even Kahlo was dismissed as a local amateur, while English-language books on Mexican art could be found only in secondhand book stores.

Back in the 1930s and 1940s - a period of artistic interchange between the US and Mexico - Hollywood stars such as Edward G Robinson, Merle Oberon and Dolores del Rio snapped up Mexican art. In 1938, Edward G Robinson bought four Kahlos for $200 each - the 31-year-old painter's first major sale - while other enthusiasts included Edgar J Kaufmann, an industrialist, and Jacques Gelman, a European-born film producer who, with his wife Natasha, amassed a collection of 20th-century Mexican art.

Artistic taste changed, however, in the 1950s, when the Cold War led collectors to turn away from work that promoted socialist values. John D Rockefeller ordered workers to smash Diego Rivera's Man at the Crossroads - painted for the Rockefeller Centre in New York - when the artist refused to remove a portrait of Lenin. Kahlo's political hero, meanwhile, was Stalin. But, more importantly, the rise of post-war abstract expressionists such as Mark Rothko and Franz Kline (whose Crow Dancer fetched $6.4 million at Christie's post-war and contemporary art sale in New York last month) made the magic surrealism of Mexican art seem old-fashioned.

"I think that in the perverse way that market psychology operates, people began to respect the Mexican market once more when Frida Kahlo's prices started to climb," says Martin. The Tree of Hope, the first Kahlo to be sold at Sotheby's, in the late 1970s, did not even reach its lower estimate of $20,000. But the swell of public interest in Kahlo - a mythic creature of her own creation - combined with the introduction of Latin American sales in New York revived interest in Mexico's rich artistic tradition.

In 1990, Kahlo's Diego and I (1949), featuring a weeping Kahlo with Diego Rivera's image in her forehead, became the first Latin American painting to sell for more than $1 million. Charles Saatchi promptly asked a dealer to find him 10 or 12 self-portraits, but backed off when faced with a $3 million price tag for a self-portrait from 1940.

No Frida Kahlos were up for sale at last month's bi-annual Latin American auctions in New York, which also included 18th- and 19th-century colonial paintings. Sotheby's had a couple of important Riveras, once of which - La ofrenda (1928) - sold for $1.6 million. But while modern Mexican masters such as Maria Izquierdo, 64-year-old Francisco Toledo (the subject of a retrospective at the Whitechapel in 2000) and Gunther Gerzso can reach up to $500,000, only the colourful, textured paintings by Rufino Tamayo, who died in 1991, have sold for over $2 million,

Kahlo, meanwhile, remains by far the most expensive Mexican artist - indeed, the dearest in the whole of Latin America. Recognised even by those with scant interest in art, her work gives a collector instant status. And as Thomas Hoving, an ex-director of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, famously said: "Art is money-sexy-social-climbing fantastic."

June 10, 2005

Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo:

-I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

-The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

-I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

-The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

June 9, 2005

Why did Frida paint herself?

Frida Kahlo

Why did Frida paint herself? Her preferred exercise seems to have been shaping and perpetuating the image the mirror returned, enriched by her own art and imagination. Her friend, Alejandro Gomez Arias, a Mexican writer, to whom she gave her first self-portrait, commented: "Frida painted as a final means of surviving, of enduring, of conquering death." On the other hand Frida herself answered this question by saying, "I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone. Because I am the person I know best."

[Espacio, Art Magazine 1983]

Why did Frida paint herself? Her preferred exercise seems to have been shaping and perpetuating the image the mirror returned, enriched by her own art and imagination. Her friend, Alejandro Gomez Arias, a Mexican writer, to whom she gave her first self-portrait, commented: "Frida painted as a final means of surviving, of enduring, of conquering death." On the other hand Frida herself answered this question by saying, "I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone. Because I am the person I know best."

[Espacio, Art Magazine 1983]

Frida Kahlo Exhibition Opens at Tate Modern

LONDON, ENGLAND.- , The first major exhibition in over twenty years devoted to the work of the celebrated Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907 -1954) will open today at Tate Modern. The exhibition is sponsored by HSBC, who are sponsoring a major arts project for the first time. Frida Kahlo is now regarded as one of the most influential and important artists of the twentieth century. She lived and worked during a time of incredible social and cultural upheaval in Mexico. Featuring more than seventy pieces, including many iconic oil paintings, as well as some lesser known early watercolours, drawings and oils, the exhibition will enable a comprehensive investigation of her artistic career.

Kahlo began painting after a serious traffic accident in her late teens led to frequent hospital visits and surgery. Her complex works combine profoundly personal subject matter with references to medical and anatomical imagery as well as Aztec, Colonial, and Mexican popular and folkloric arts and crafts. Broadly chronological in form, the exhibition will examine how Kahlo exploited the history and traditions of painting including still life, portraiture, narrative and religious paintings and subverted these for her own ends, infusing them with powerful political insight, humour and candid self-analysis.

Drawing from key international collections, this is the first exhibition in this country ever to be dedicated solely to the work of the artist. It explores her contribution to the art of self-portraiture and includes Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera 1931, a marriage portrait that graphically depicts the dominant human relationship in her life, and which also reveals her interest in naïve popular painting; The Little Deer, 1946 which depicts her as a wounded stag in a forest; and Self- Portrait with Monkey 1938. The centrepiece of the exhibition is The Two Fridas 1939, one of her largest and most ambitious canvases. Combining surrealist tendencies with acute anatomical and psychological insight, it depicts a doubled self, one European, the other Mexican, one loved, the other unloved. These works demonstrate a remarkable richness of detail and symbol, as well as hinting at the pain behind Kahlo’s unsmiling mask of a face...artdaily.com

Click the Title Link to continue.

Kahlo began painting after a serious traffic accident in her late teens led to frequent hospital visits and surgery. Her complex works combine profoundly personal subject matter with references to medical and anatomical imagery as well as Aztec, Colonial, and Mexican popular and folkloric arts and crafts. Broadly chronological in form, the exhibition will examine how Kahlo exploited the history and traditions of painting including still life, portraiture, narrative and religious paintings and subverted these for her own ends, infusing them with powerful political insight, humour and candid self-analysis.

Drawing from key international collections, this is the first exhibition in this country ever to be dedicated solely to the work of the artist. It explores her contribution to the art of self-portraiture and includes Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera 1931, a marriage portrait that graphically depicts the dominant human relationship in her life, and which also reveals her interest in naïve popular painting; The Little Deer, 1946 which depicts her as a wounded stag in a forest; and Self- Portrait with Monkey 1938. The centrepiece of the exhibition is The Two Fridas 1939, one of her largest and most ambitious canvases. Combining surrealist tendencies with acute anatomical and psychological insight, it depicts a doubled self, one European, the other Mexican, one loved, the other unloved. These works demonstrate a remarkable richness of detail and symbol, as well as hinting at the pain behind Kahlo’s unsmiling mask of a face...artdaily.com

Click the Title Link to continue.

June 4, 2005

Art Market Watch, Artnet - New York,NY,USA

SOTHEBY'S DOES $12.7 MILLION IN LATIN AMERICAN ART

Sotheby's New York held its two-day spring sale of Latin American art on May 24-25, 2005, and tallied a grand total of $12,756,400, with 78 percent of the lots finding buyers. The highlight of the sale was Diego Rivera's 1928 La Ofrenda, a naïve but haunting rendering of two children in the jungle, which sold for $1,584,000.

Sotheby's new Latin American art chief Carmen Melián noted strength across all three major categories -- the Mexican masters, Southern School Constructivists and the Kinetic movement -- as well as strong prices for Colonial works.

In a distribution that reflects Melián's analysis, the auction set new records for five artists: Joaquín Torres-García ($940,000, for his 1935 Constructivo en Blanco y Negro); Alejandro Otero ($162,000, paid for a 1957 Kinetic art construction); Carlos Cruz Diez ($57,000, for Physicromie #245, another Kinetic construction, this one from 1966); Juan Pedro López ($144,000 for La Virgen, Reina y Pastora de la Iglesia, 1780); and Fray Alonso López de Herrera ($102,000, for his 1640 Immaculate Conception, a ca. 21 x 15 in. oil painting on copper).

$8.3 MILLION FOR CHRISTIE'S LATIN AMERICAN ART

The Christie's New York Latin American auction on May 25-26, 2004, totaled $8,355,160. Of 182 lots offered, 111 sold, or about 61 percent. The top lot was Rufino Tamayo's Discusión acalorada (1953), which was bought for $867,200 (est. $500,000-$700,000); it came from the collection of Ruth and Harvey Kaplan. Fernando Botero's 1976 bronze sculpture, Sitting Woman, sold for $688,000 (est. $400,000-$500,000), a new auction record for a sculpture by the artist.

Virgilio Garza, head of the Latin American art department at Christie's, noted that the sale established new world auction records for several Latin American artists, including Raúl Anguiano ($156,000, for La espina, a rough-hewn rendering of a saint-like figure digging a splinter out of his foot with a knife); Pedro Coronel ($307,200 for La primavera, 1948); Enio Iommi ($24,000, for a Caldersque abstract wire construction, 1947); Victor Rodríguez ($20,400, for 2004 Photo Realist painting of a weeping woman in profile); and Carlos Amorales ($18,000, for a 2004 oil of a crow wearing a human skull on its head).

For complete, illustrated auction results, see Artnet's signature Fine Art Auctions Report.

Sotheby's New York held its two-day spring sale of Latin American art on May 24-25, 2005, and tallied a grand total of $12,756,400, with 78 percent of the lots finding buyers. The highlight of the sale was Diego Rivera's 1928 La Ofrenda, a naïve but haunting rendering of two children in the jungle, which sold for $1,584,000.

Sotheby's new Latin American art chief Carmen Melián noted strength across all three major categories -- the Mexican masters, Southern School Constructivists and the Kinetic movement -- as well as strong prices for Colonial works.

In a distribution that reflects Melián's analysis, the auction set new records for five artists: Joaquín Torres-García ($940,000, for his 1935 Constructivo en Blanco y Negro); Alejandro Otero ($162,000, paid for a 1957 Kinetic art construction); Carlos Cruz Diez ($57,000, for Physicromie #245, another Kinetic construction, this one from 1966); Juan Pedro López ($144,000 for La Virgen, Reina y Pastora de la Iglesia, 1780); and Fray Alonso López de Herrera ($102,000, for his 1640 Immaculate Conception, a ca. 21 x 15 in. oil painting on copper).

$8.3 MILLION FOR CHRISTIE'S LATIN AMERICAN ART

The Christie's New York Latin American auction on May 25-26, 2004, totaled $8,355,160. Of 182 lots offered, 111 sold, or about 61 percent. The top lot was Rufino Tamayo's Discusión acalorada (1953), which was bought for $867,200 (est. $500,000-$700,000); it came from the collection of Ruth and Harvey Kaplan. Fernando Botero's 1976 bronze sculpture, Sitting Woman, sold for $688,000 (est. $400,000-$500,000), a new auction record for a sculpture by the artist.

Virgilio Garza, head of the Latin American art department at Christie's, noted that the sale established new world auction records for several Latin American artists, including Raúl Anguiano ($156,000, for La espina, a rough-hewn rendering of a saint-like figure digging a splinter out of his foot with a knife); Pedro Coronel ($307,200 for La primavera, 1948); Enio Iommi ($24,000, for a Caldersque abstract wire construction, 1947); Victor Rodríguez ($20,400, for 2004 Photo Realist painting of a weeping woman in profile); and Carlos Amorales ($18,000, for a 2004 oil of a crow wearing a human skull on its head).

For complete, illustrated auction results, see Artnet's signature Fine Art Auctions Report.

June 2, 2005

Dark time for U.S. Mexicans by Francisco Zerme

Inside Bay Area-Daily Review Online.

MOST PEOPLE now would agree that the Japanese internments during World War II represent a dark chapter in the history of the United States. To a degree, apologies and reparations have mollified these memories, I hope, at least with the majority of our Japanese-American brothers.

Just prior to that, however, there was another dark episode, one that has not received the attention of the internments. It is the Mexican Repatriation, which took place from 1929 to 1944. That was the Depression, the Dust Bowl years, so excellently portrayed in John Steinbeck's "The Grapes of Wrath."

Everyone wanted to move to the Western states, especially California. There was plenty of room. There were not, however, enough jobs for the new arrivals. Something had to be done. President Hoover came up with an idea that would create jobs for the new arrivals. It was simple. A train ride for the Mexicans living in the West. All Mexicans. Back to Mexico. Regardless of their resident status. It was enforced by the local authorities.

Now, at that time, illegal migration existed, but it did not cause the upheaval or the Arizonan vigilantism of today. Personally, I accept immigration because the greatness of this country of ours is due, in large part, to it.

Click title link to continue.

MOST PEOPLE now would agree that the Japanese internments during World War II represent a dark chapter in the history of the United States. To a degree, apologies and reparations have mollified these memories, I hope, at least with the majority of our Japanese-American brothers.

Just prior to that, however, there was another dark episode, one that has not received the attention of the internments. It is the Mexican Repatriation, which took place from 1929 to 1944. That was the Depression, the Dust Bowl years, so excellently portrayed in John Steinbeck's "The Grapes of Wrath."

Everyone wanted to move to the Western states, especially California. There was plenty of room. There were not, however, enough jobs for the new arrivals. Something had to be done. President Hoover came up with an idea that would create jobs for the new arrivals. It was simple. A train ride for the Mexicans living in the West. All Mexicans. Back to Mexico. Regardless of their resident status. It was enforced by the local authorities.

Now, at that time, illegal migration existed, but it did not cause the upheaval or the Arizonan vigilantism of today. Personally, I accept immigration because the greatness of this country of ours is due, in large part, to it.

Click title link to continue.

The city of "Guanajuato," and Guanajuato the state history

HISTORY

In the pre-Hispanic period the territory now occupied by the city of Guanajuato was chiefly inhabited by nomadic tribes generically known as Chichimecas who lived by hunting and gathering.

The city of Guanajuato was founded by the Spanish in the 16th century. Don Rodrigo Vazquez was granted the central part of the state of Guanajuato where he started looking for silver and other precious metals. Several mines were opened and indian were made slaves and put to work to extract the precious metal from the earth. Guanajuato soon became the silver-mining centre of the world. The spaniards also took advantage of the fertile plains in the region. Several fruits and vegetables were brought from Spain and cultivated in Guanajuato to realize bumper crops.

In the sixteenth century, the colonists built theatres, churches, museums, squares, markets and side streets. Universities were built and artists and musicians were encouraged. Many of these monuments still exist today from which cultural manifestations surge out. This period of bliss lasted till the 19th century.

Mexican war of Independence

Father Miguel Hidalgo instigated the Indian and mestizo population to revolt against the spaniards. In September 1810, he and his band of revolutionaries encountered stiff resistance at while trying to win Guanajuato. Several thousand soldiers were killed in this bloody battle but the rebels managed to win the city. Father Hidalgo was later captured and executed by firing squad on July 31, 1811. After eleven more years of fighting Mexico won independence from Spain on August 24, 1821. Guanajuato was named 'Cultural Heritage of Humanity, by UNESCO in 1988, for the magnificent colonial buildings that make up its architecture.

In the pre-Hispanic period the territory now occupied by the city of Guanajuato was chiefly inhabited by nomadic tribes generically known as Chichimecas who lived by hunting and gathering.

The city of Guanajuato was founded by the Spanish in the 16th century. Don Rodrigo Vazquez was granted the central part of the state of Guanajuato where he started looking for silver and other precious metals. Several mines were opened and indian were made slaves and put to work to extract the precious metal from the earth. Guanajuato soon became the silver-mining centre of the world. The spaniards also took advantage of the fertile plains in the region. Several fruits and vegetables were brought from Spain and cultivated in Guanajuato to realize bumper crops.

In the sixteenth century, the colonists built theatres, churches, museums, squares, markets and side streets. Universities were built and artists and musicians were encouraged. Many of these monuments still exist today from which cultural manifestations surge out. This period of bliss lasted till the 19th century.

Mexican war of Independence

Father Miguel Hidalgo instigated the Indian and mestizo population to revolt against the spaniards. In September 1810, he and his band of revolutionaries encountered stiff resistance at while trying to win Guanajuato. Several thousand soldiers were killed in this bloody battle but the rebels managed to win the city. Father Hidalgo was later captured and executed by firing squad on July 31, 1811. After eleven more years of fighting Mexico won independence from Spain on August 24, 1821. Guanajuato was named 'Cultural Heritage of Humanity, by UNESCO in 1988, for the magnificent colonial buildings that make up its architecture.

May 29, 2005

The web-site: "Great Masters of Mexican Folk Art," From the Collection of Fomento Cultural Banamex

Excellent web site, with a limited number of artists that respresent the vast number of working artists who continue to fuse the traditional with contemporary life, as it has always done. Art for indigenous artists is part of the ever-changing timeless present.

May 26, 2005

The Labyrinth of Solitutde, Octavio Paz

"All of us, at some moment, have had a vision of our existence a something unique, untransferable and very precious. This revelation almost always takes place during adolescence. Self-discovery is above all the realization that we are alone: it is the opening of an impalpable, transparent wall -- that of our consciousness -- between the world and ourselves. It is true that we sense our aloneness almost as soon as we are born, but children and adults can transcend their solitude and forget themselves in games and work. The adolescent, however vacillates between infancy and youth, halting for a moment before the infinite richness of the world. He is astonished at the fact of his being, and this astonishment leads to reflection: as he leans over the river of his consciousness, he asks himself if the face that appears there, disfigured by the water, is his own. The singularity of his being, which is pure sensation in children, becomes a problem and a question."

May 25, 2005

Portals to the World: Library of Congress Subject Experts on mExico

Every conceivable link about research on Mexico. Amazing.

May 24, 2005

The Mexican Cultural Institute of New York

Interesting site promoting the Mexican Arts.

Their mission statement is to "promote cultural expressions, art, education, science, technology and research of Mexico, as well as to foster the presence of the most innovative and contemporary cultural output from Mexico in New York and the United States in general."

Their mission statement is to "promote cultural expressions, art, education, science, technology and research of Mexico, as well as to foster the presence of the most innovative and contemporary cultural output from Mexico in New York and the United States in general."

Mexico Now, a Month-Long Festival to Celebrate Mexico’s Thriving Contemporary Arts Scene

From November 1st to 28, Mexico Now will flood leading arts venues in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens with the works and performances of nearly 100 of Mexico’s most renowned contemporary artists will participate in concerts, dance performances, exhibits and film screenings. For event information visit: www.mexiconowfestival.org

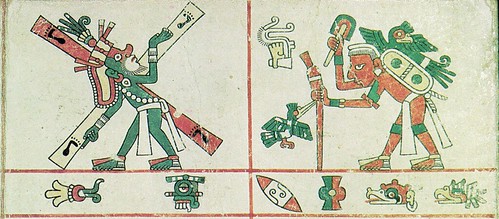

The Aztec Empire, Guggenheim Exhibition

The The most comprehensive survey of art and culture of the Aztecs ever assembled outside Mexico. More than 450 works drawn from major collections in the United States and Mexico, including many important works never before seen outside of Mexico, are featured in The Aztec Empire Exhibit.

may celebration of the santa cruz de calledron

Photos of the celebration of Sant Cruz in San Miguel.

Celebration of the Santa Cruz

Otomi rituals and celebrations: Crosses, Ancestors, and Resurrection

Journal of American Folklore, Fall 2000 by Correa, Phyllis M

...At the time of the Spanish conquest, a separate ethnic and linguistic group from the Nahuatl (of which the Aztecs were members), the Otomi, with a reputation for military prowess and acculturated into the general Mesoamerican cultural pattern of high civilization, occupied the northern and eastern border zones of the Aztec and Tarascan Empires. As subjects of these empires, the Otomi acted as protectors of the borders against incursions by the nomadic groups generically called Chichimecs to the north and east and also appear to have interacted with them for trade purposes as well. The area between the two Sierra Madre mountain ranges north of the Mesoamerican cultural area was mainly occupied by those nomadic groups and was called the Gran Chichimeca (Great Chichimec Region) by the Spanish. The location where San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende) was established held strategic importance for the expansion of Spanish domination into an area not under the control of the prehispanic empires and also played an important economic and commercial role throughout the colonial period as a supply center for the gold and silver mines discovered in Guanajuato and Zacatecas to the north.

Otomies from Jilotepec Province, to the north of the Valley of Mexico, were active participants in the conquest of both Queretaro and Guanajuato during the early colonial period as allies of the Spanish and provided the earliest colonizers, who, together with groups of pacified Chichimecs, created a network integrating local communities into a broader social, economic, and political system that also served as the basis for a regional identity. Today, this network is maintained primarily through the reciprocal participation in religious celebrations throughout the area and the existence of a hierarchy of groups and individuals involved in the organization of these celebrations. The Laja River, a tributary of the Lerma-Santiago River system, lies four kilometers to the west of San Miguel de Allende and was the main zone of Otomi occupation, including several traditional barrios of the city itself In recent decades, the use of the Otomi language has virtually disappeared in Guanajuato, and it is virtually impossible to distinguish the Otomi from mestizo peasants and residents of marginal urban neighborhoods who generally do not participate in the religious complex.1

The rituals and ceremonies described in this article that form part of the Otomi religious complex took place during Holy Week in the family chapel of Don Agapito R., a former resident of the ranch of Tirado, which was inundated by a large dam built in the late 1960s. When forced to leave, Don Agapito, who is now close to 90 years old, purchased a large lot on the outskirts of town near the railroad station where he and his extended family reside. A small chapel was built to house religious objects he recovered from the two chapels of Tirado consisting primarily of a number of crosses; statues of Saints Michael and James, to whom the chapels of the ranch were dedicated; and several retablos of saints. Retablos are religious pictures of saints drawn on tin or scenes describing the miraculous deed of a saint to whom the petitioner turned in a time of need. The second type can be found on the walls of many churches and shrines offered as an expression of gratitude to a specific image.

Crosses, with distinct characteristics and of differing types, are central to Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the cross as a symbol of the four winds and four cardinal directions, as well as the veneration of the ancestors and their relationship to fire, the sun, military conquest, and sacrifice. Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint James, the patron saint of the Spanish reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, are both important figures within the Otomi religious configuration as divine warriors. Of the retablos in Don Agapito's chapel, one depicting San Isidro Labrador, called the demandita (literally, the "little petition"), is the most important. San Isidro, whose feast day is 15 May, was celebrated elaborately in the former community of Tirado and is the principal patron saint of numerous rural communities around San Miguel.2 Apparently a large oil painting of this saint was taken by another member of the community and is housed in their family chapel.

Don Agapito and his family perform rituals and celebrations on various occasions throughout the year, and in September, during the celebrations to Saint Michael the Archangel, the patron saint of the city, they continue to make the offering for the ancestors in the name of the community of Tirado. According to Don Agapito, as long as he lives, he will maintain these traditions and hopefully his family will continue them. To quote him, "Everything changes, but the traditions go on. If one person is missing, there is another 'to pick up the word.'" This statement reflects the central thesis of this article: that popular religion in Mexico, while retaining a central core of elements and beliefs that forms the basis for its ideology and cosmovision, is not conservative or static but, rather, adapts in response to changing circumstances and is continually being created and re-created as traditions are transmitted both orally and through active participation in rituals and ceremonies to new generations. Furthermore, this central core of elements and beliefs is more closely related to a prehispanic configuration, in this case Otomi, and Catholic elements adopted or appropriated have been reworked to conform to that general conceptualization. The central issues to be examined revolve around questions of continuity (what remains stable and why) and change, which in this particular instance was the dissolution of a rural community as the result of a state project (the building of a dam). It is hoped that this example can shed some light on how external pressures can disrupt the community-wide organization of religious celebrations and yet, on an individual and familial level, can be maintained and transmitted. To understand the context of Otomi popular religious traditions in the zone within which the specific rituals analyzed are performed, it is first necessary to have a general overview of the ceremonies, symbolic elements, and cosmology as manifested in this area of central Mexico.

The Sacred Cross of Calder6n Pass

The primary focal point of popular religion among the Otomi who inhabit the communities along the Laja River in the State of Guanajuato, including the city of San Miguel de Allende, is the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass. This particular cross integrates a number of traditional urban neighborhoods and rural communities both within the township and throughout much of the central highlands, primarily the Bajio region to the south,3 in a network based on the worship of crosses, other religious saints and images, and sacred places.

According to the story transmitted from generation to generation, on 14 September 1531, non-Christianized Chichimecs confronted Christianized Otomi and Chichimec captains in an streambed near Calderon Pass in a bloody battle that lasted 15 days and nights until suddenly it grew dark and a shining cross appeared in the sky. Upon seeing this supernatural sign, the non-Christianized natives stopped fighting and cried out, "El es Dios" [He is God]. The supernatural appearance of the cross meant that they should surrender and accept the Catholic faith, making peace with their native brothers who had fought against them. A cross was carved out of stone and taken to the high part of the pass where a chapel was built.

This stone cross is about four feet tall and rests on a small pedestal. It has been covered with a thin layer of tin that is painted a dark burnished brown and covered with diverse figures representing the passion and death of Christ, two human figures who look like native dancers, the sun and moon at each point of the horizontal axis, a bloodied dagger at the base, the sacred heart of Christ, and a pair of severed feet and severed hands with the palms showing. Despite their relationship to Christian beliefs (the hands and feet of Christ had nails driven in them when he was crucified, and his heart was pierced to be sure he was dead), in prehispanic times the feet and hands of sacrificial victims were sent to the principal lords, while the head and heart could only be eaten by the high priests or emperor (Gonzalez Torres 1994:294). On a short crosspiece at the very top of the cross is a mirror encrusted in the stone with the letters "I N R I" The cross itself is topped off with a small metal crown. A very important feature of the cross is the tiny head of Christ carved from wood and inserted in a hollow precisely at the intersection of the two axes, making it look as though the figure of Christ is completely enveloped by the cross. This style of the Christ figure being inserted within the material of the cross, whether it is made of wood or stone, is relatively common in the areas inhabited by the Otomi. The wooden crosses of this type are also covered almost completely with mirrors painted with the figures of the passion of Christ and, in some cases, also showing the hands, feet, and heart of Christ.