Interesting site promoting the Mexican Arts.

Their mission statement is to "promote cultural expressions, art, education, science, technology and research of Mexico, as well as to foster the presence of the most innovative and contemporary cultural output from Mexico in New York and the United States in general."

May 24, 2005

Mexico Now, a Month-Long Festival to Celebrate Mexico’s Thriving Contemporary Arts Scene

From November 1st to 28, Mexico Now will flood leading arts venues in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens with the works and performances of nearly 100 of Mexico’s most renowned contemporary artists will participate in concerts, dance performances, exhibits and film screenings. For event information visit: www.mexiconowfestival.org

The Aztec Empire, Guggenheim Exhibition

The The most comprehensive survey of art and culture of the Aztecs ever assembled outside Mexico. More than 450 works drawn from major collections in the United States and Mexico, including many important works never before seen outside of Mexico, are featured in The Aztec Empire Exhibit.

may celebration of the santa cruz de calledron

Photos of the celebration of Sant Cruz in San Miguel.

Celebration of the Santa Cruz

Otomi rituals and celebrations: Crosses, Ancestors, and Resurrection

Journal of American Folklore, Fall 2000 by Correa, Phyllis M

...At the time of the Spanish conquest, a separate ethnic and linguistic group from the Nahuatl (of which the Aztecs were members), the Otomi, with a reputation for military prowess and acculturated into the general Mesoamerican cultural pattern of high civilization, occupied the northern and eastern border zones of the Aztec and Tarascan Empires. As subjects of these empires, the Otomi acted as protectors of the borders against incursions by the nomadic groups generically called Chichimecs to the north and east and also appear to have interacted with them for trade purposes as well. The area between the two Sierra Madre mountain ranges north of the Mesoamerican cultural area was mainly occupied by those nomadic groups and was called the Gran Chichimeca (Great Chichimec Region) by the Spanish. The location where San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende) was established held strategic importance for the expansion of Spanish domination into an area not under the control of the prehispanic empires and also played an important economic and commercial role throughout the colonial period as a supply center for the gold and silver mines discovered in Guanajuato and Zacatecas to the north.

Otomies from Jilotepec Province, to the north of the Valley of Mexico, were active participants in the conquest of both Queretaro and Guanajuato during the early colonial period as allies of the Spanish and provided the earliest colonizers, who, together with groups of pacified Chichimecs, created a network integrating local communities into a broader social, economic, and political system that also served as the basis for a regional identity. Today, this network is maintained primarily through the reciprocal participation in religious celebrations throughout the area and the existence of a hierarchy of groups and individuals involved in the organization of these celebrations. The Laja River, a tributary of the Lerma-Santiago River system, lies four kilometers to the west of San Miguel de Allende and was the main zone of Otomi occupation, including several traditional barrios of the city itself In recent decades, the use of the Otomi language has virtually disappeared in Guanajuato, and it is virtually impossible to distinguish the Otomi from mestizo peasants and residents of marginal urban neighborhoods who generally do not participate in the religious complex.1

The rituals and ceremonies described in this article that form part of the Otomi religious complex took place during Holy Week in the family chapel of Don Agapito R., a former resident of the ranch of Tirado, which was inundated by a large dam built in the late 1960s. When forced to leave, Don Agapito, who is now close to 90 years old, purchased a large lot on the outskirts of town near the railroad station where he and his extended family reside. A small chapel was built to house religious objects he recovered from the two chapels of Tirado consisting primarily of a number of crosses; statues of Saints Michael and James, to whom the chapels of the ranch were dedicated; and several retablos of saints. Retablos are religious pictures of saints drawn on tin or scenes describing the miraculous deed of a saint to whom the petitioner turned in a time of need. The second type can be found on the walls of many churches and shrines offered as an expression of gratitude to a specific image.

Crosses, with distinct characteristics and of differing types, are central to Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the cross as a symbol of the four winds and four cardinal directions, as well as the veneration of the ancestors and their relationship to fire, the sun, military conquest, and sacrifice. Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint James, the patron saint of the Spanish reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, are both important figures within the Otomi religious configuration as divine warriors. Of the retablos in Don Agapito's chapel, one depicting San Isidro Labrador, called the demandita (literally, the "little petition"), is the most important. San Isidro, whose feast day is 15 May, was celebrated elaborately in the former community of Tirado and is the principal patron saint of numerous rural communities around San Miguel.2 Apparently a large oil painting of this saint was taken by another member of the community and is housed in their family chapel.

Don Agapito and his family perform rituals and celebrations on various occasions throughout the year, and in September, during the celebrations to Saint Michael the Archangel, the patron saint of the city, they continue to make the offering for the ancestors in the name of the community of Tirado. According to Don Agapito, as long as he lives, he will maintain these traditions and hopefully his family will continue them. To quote him, "Everything changes, but the traditions go on. If one person is missing, there is another 'to pick up the word.'" This statement reflects the central thesis of this article: that popular religion in Mexico, while retaining a central core of elements and beliefs that forms the basis for its ideology and cosmovision, is not conservative or static but, rather, adapts in response to changing circumstances and is continually being created and re-created as traditions are transmitted both orally and through active participation in rituals and ceremonies to new generations. Furthermore, this central core of elements and beliefs is more closely related to a prehispanic configuration, in this case Otomi, and Catholic elements adopted or appropriated have been reworked to conform to that general conceptualization. The central issues to be examined revolve around questions of continuity (what remains stable and why) and change, which in this particular instance was the dissolution of a rural community as the result of a state project (the building of a dam). It is hoped that this example can shed some light on how external pressures can disrupt the community-wide organization of religious celebrations and yet, on an individual and familial level, can be maintained and transmitted. To understand the context of Otomi popular religious traditions in the zone within which the specific rituals analyzed are performed, it is first necessary to have a general overview of the ceremonies, symbolic elements, and cosmology as manifested in this area of central Mexico.

The Sacred Cross of Calder6n Pass

The primary focal point of popular religion among the Otomi who inhabit the communities along the Laja River in the State of Guanajuato, including the city of San Miguel de Allende, is the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass. This particular cross integrates a number of traditional urban neighborhoods and rural communities both within the township and throughout much of the central highlands, primarily the Bajio region to the south,3 in a network based on the worship of crosses, other religious saints and images, and sacred places.

According to the story transmitted from generation to generation, on 14 September 1531, non-Christianized Chichimecs confronted Christianized Otomi and Chichimec captains in an streambed near Calderon Pass in a bloody battle that lasted 15 days and nights until suddenly it grew dark and a shining cross appeared in the sky. Upon seeing this supernatural sign, the non-Christianized natives stopped fighting and cried out, "El es Dios" [He is God]. The supernatural appearance of the cross meant that they should surrender and accept the Catholic faith, making peace with their native brothers who had fought against them. A cross was carved out of stone and taken to the high part of the pass where a chapel was built.

This stone cross is about four feet tall and rests on a small pedestal. It has been covered with a thin layer of tin that is painted a dark burnished brown and covered with diverse figures representing the passion and death of Christ, two human figures who look like native dancers, the sun and moon at each point of the horizontal axis, a bloodied dagger at the base, the sacred heart of Christ, and a pair of severed feet and severed hands with the palms showing. Despite their relationship to Christian beliefs (the hands and feet of Christ had nails driven in them when he was crucified, and his heart was pierced to be sure he was dead), in prehispanic times the feet and hands of sacrificial victims were sent to the principal lords, while the head and heart could only be eaten by the high priests or emperor (Gonzalez Torres 1994:294). On a short crosspiece at the very top of the cross is a mirror encrusted in the stone with the letters "I N R I" The cross itself is topped off with a small metal crown. A very important feature of the cross is the tiny head of Christ carved from wood and inserted in a hollow precisely at the intersection of the two axes, making it look as though the figure of Christ is completely enveloped by the cross. This style of the Christ figure being inserted within the material of the cross, whether it is made of wood or stone, is relatively common in the areas inhabited by the Otomi. The wooden crosses of this type are also covered almost completely with mirrors painted with the figures of the passion of Christ and, in some cases, also showing the hands, feet, and heart of Christ.

Calderon Pass is sacred not only because it overlooks a river valley to the north and another to the south, a location that forms a natural opening and is also a sort of natural crossroads, but also because of its location near where the battle of 1531 took place. Many important locations in Otomi sacred geography have been blessed by blood being shed in a violent way. Energy emanating from the souls of the dead creates an opening to communicate with supernatural beings and provides the power used by practitioners to perform magic. These locations as well as the tops of mountains, crossroads, caves, and points of the five cardinal directions are all called puertos, which literally translated means "passages" or "openings."4

To better understand the general complex of Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the worship of the Sacred Cross of Calderon and the rituals described in the family chapel of Don Agapito, I will briefly describe the two celebrations coinciding with the beginning and end of the annual agricultural cycle in which the cross plays an important role: 3 May and the festivities for Saint Michael the Archangel at the end of September.

Celebrations for the Sacred Cross during the Month of May

The Day of the Sacred Cross, on 3 May, begins a cycle of celebrations for crosses in homes, in chapels, on hills, and at roadside shrines throughout the month in rural communities and urban neighborhoods. On the night of 2 May, the cycle is initiated with velaciones (nightlong vigil characteristic of Otomi celebrations with clear connotations of being a wake for the dead) in many chapels, including the chapel at Calderon Pass. During these nightlong vigils, members of different communities arrive in groups to honor the cross, carrying their own images, crosses, and offerings such as flowers and candles. Upon their arrival, they are received by the individuals in charge of the celebration, and together they enter the chapel accompanied by the clanging of the chapel bell to be blessed (or more accurately, "cleansed," for the ritual is called limpia) by their spiritual leaders and to make their offerings of candles and flowers. Because people travel from other communities, they come prepared to spend the night, and usually food, coffee, and liquor are offered. During the night, copal (a native incense made from pine resin) is burned, and the people sing hymns calling on the four winds, four cardinal directions, and the animas, or souls, of the ancestors to protect and bless them, accompanied by musicians who play mandolin-like instruments made out of armadillo shells (called conchas).5

Because the cult has been relatively isolated and because of the strong magical and shamanic elements involved, outsiders, including other peasants in the township who do not participate in the cult itself, frequently believe the participants are witches and should be avoided. Individuals who practice black magic also consider the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass as their principal source of supernatural energy, but those who actively participate in the cult rarely claim to do harm to others. In fact, it is considered to be very harmful if such people participate in the rituals and ceremonies because the celebrations, particularly the ones in September, emphasize reconciliation and the forgiveness of offenses rather than vengeance.

Journal of American Folklore, Fall 2000 by Correa, Phyllis M

...At the time of the Spanish conquest, a separate ethnic and linguistic group from the Nahuatl (of which the Aztecs were members), the Otomi, with a reputation for military prowess and acculturated into the general Mesoamerican cultural pattern of high civilization, occupied the northern and eastern border zones of the Aztec and Tarascan Empires. As subjects of these empires, the Otomi acted as protectors of the borders against incursions by the nomadic groups generically called Chichimecs to the north and east and also appear to have interacted with them for trade purposes as well. The area between the two Sierra Madre mountain ranges north of the Mesoamerican cultural area was mainly occupied by those nomadic groups and was called the Gran Chichimeca (Great Chichimec Region) by the Spanish. The location where San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende) was established held strategic importance for the expansion of Spanish domination into an area not under the control of the prehispanic empires and also played an important economic and commercial role throughout the colonial period as a supply center for the gold and silver mines discovered in Guanajuato and Zacatecas to the north.

Otomies from Jilotepec Province, to the north of the Valley of Mexico, were active participants in the conquest of both Queretaro and Guanajuato during the early colonial period as allies of the Spanish and provided the earliest colonizers, who, together with groups of pacified Chichimecs, created a network integrating local communities into a broader social, economic, and political system that also served as the basis for a regional identity. Today, this network is maintained primarily through the reciprocal participation in religious celebrations throughout the area and the existence of a hierarchy of groups and individuals involved in the organization of these celebrations. The Laja River, a tributary of the Lerma-Santiago River system, lies four kilometers to the west of San Miguel de Allende and was the main zone of Otomi occupation, including several traditional barrios of the city itself In recent decades, the use of the Otomi language has virtually disappeared in Guanajuato, and it is virtually impossible to distinguish the Otomi from mestizo peasants and residents of marginal urban neighborhoods who generally do not participate in the religious complex.1

The rituals and ceremonies described in this article that form part of the Otomi religious complex took place during Holy Week in the family chapel of Don Agapito R., a former resident of the ranch of Tirado, which was inundated by a large dam built in the late 1960s. When forced to leave, Don Agapito, who is now close to 90 years old, purchased a large lot on the outskirts of town near the railroad station where he and his extended family reside. A small chapel was built to house religious objects he recovered from the two chapels of Tirado consisting primarily of a number of crosses; statues of Saints Michael and James, to whom the chapels of the ranch were dedicated; and several retablos of saints. Retablos are religious pictures of saints drawn on tin or scenes describing the miraculous deed of a saint to whom the petitioner turned in a time of need. The second type can be found on the walls of many churches and shrines offered as an expression of gratitude to a specific image.

Crosses, with distinct characteristics and of differing types, are central to Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the cross as a symbol of the four winds and four cardinal directions, as well as the veneration of the ancestors and their relationship to fire, the sun, military conquest, and sacrifice. Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint James, the patron saint of the Spanish reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, are both important figures within the Otomi religious configuration as divine warriors. Of the retablos in Don Agapito's chapel, one depicting San Isidro Labrador, called the demandita (literally, the "little petition"), is the most important. San Isidro, whose feast day is 15 May, was celebrated elaborately in the former community of Tirado and is the principal patron saint of numerous rural communities around San Miguel.2 Apparently a large oil painting of this saint was taken by another member of the community and is housed in their family chapel.

Don Agapito and his family perform rituals and celebrations on various occasions throughout the year, and in September, during the celebrations to Saint Michael the Archangel, the patron saint of the city, they continue to make the offering for the ancestors in the name of the community of Tirado. According to Don Agapito, as long as he lives, he will maintain these traditions and hopefully his family will continue them. To quote him, "Everything changes, but the traditions go on. If one person is missing, there is another 'to pick up the word.'" This statement reflects the central thesis of this article: that popular religion in Mexico, while retaining a central core of elements and beliefs that forms the basis for its ideology and cosmovision, is not conservative or static but, rather, adapts in response to changing circumstances and is continually being created and re-created as traditions are transmitted both orally and through active participation in rituals and ceremonies to new generations. Furthermore, this central core of elements and beliefs is more closely related to a prehispanic configuration, in this case Otomi, and Catholic elements adopted or appropriated have been reworked to conform to that general conceptualization. The central issues to be examined revolve around questions of continuity (what remains stable and why) and change, which in this particular instance was the dissolution of a rural community as the result of a state project (the building of a dam). It is hoped that this example can shed some light on how external pressures can disrupt the community-wide organization of religious celebrations and yet, on an individual and familial level, can be maintained and transmitted. To understand the context of Otomi popular religious traditions in the zone within which the specific rituals analyzed are performed, it is first necessary to have a general overview of the ceremonies, symbolic elements, and cosmology as manifested in this area of central Mexico.

The Sacred Cross of Calder6n Pass

The primary focal point of popular religion among the Otomi who inhabit the communities along the Laja River in the State of Guanajuato, including the city of San Miguel de Allende, is the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass. This particular cross integrates a number of traditional urban neighborhoods and rural communities both within the township and throughout much of the central highlands, primarily the Bajio region to the south,3 in a network based on the worship of crosses, other religious saints and images, and sacred places.

According to the story transmitted from generation to generation, on 14 September 1531, non-Christianized Chichimecs confronted Christianized Otomi and Chichimec captains in an streambed near Calderon Pass in a bloody battle that lasted 15 days and nights until suddenly it grew dark and a shining cross appeared in the sky. Upon seeing this supernatural sign, the non-Christianized natives stopped fighting and cried out, "El es Dios" [He is God]. The supernatural appearance of the cross meant that they should surrender and accept the Catholic faith, making peace with their native brothers who had fought against them. A cross was carved out of stone and taken to the high part of the pass where a chapel was built.

This stone cross is about four feet tall and rests on a small pedestal. It has been covered with a thin layer of tin that is painted a dark burnished brown and covered with diverse figures representing the passion and death of Christ, two human figures who look like native dancers, the sun and moon at each point of the horizontal axis, a bloodied dagger at the base, the sacred heart of Christ, and a pair of severed feet and severed hands with the palms showing. Despite their relationship to Christian beliefs (the hands and feet of Christ had nails driven in them when he was crucified, and his heart was pierced to be sure he was dead), in prehispanic times the feet and hands of sacrificial victims were sent to the principal lords, while the head and heart could only be eaten by the high priests or emperor (Gonzalez Torres 1994:294). On a short crosspiece at the very top of the cross is a mirror encrusted in the stone with the letters "I N R I" The cross itself is topped off with a small metal crown. A very important feature of the cross is the tiny head of Christ carved from wood and inserted in a hollow precisely at the intersection of the two axes, making it look as though the figure of Christ is completely enveloped by the cross. This style of the Christ figure being inserted within the material of the cross, whether it is made of wood or stone, is relatively common in the areas inhabited by the Otomi. The wooden crosses of this type are also covered almost completely with mirrors painted with the figures of the passion of Christ and, in some cases, also showing the hands, feet, and heart of Christ.

Calderon Pass is sacred not only because it overlooks a river valley to the north and another to the south, a location that forms a natural opening and is also a sort of natural crossroads, but also because of its location near where the battle of 1531 took place. Many important locations in Otomi sacred geography have been blessed by blood being shed in a violent way. Energy emanating from the souls of the dead creates an opening to communicate with supernatural beings and provides the power used by practitioners to perform magic. These locations as well as the tops of mountains, crossroads, caves, and points of the five cardinal directions are all called puertos, which literally translated means "passages" or "openings."4

To better understand the general complex of Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the worship of the Sacred Cross of Calderon and the rituals described in the family chapel of Don Agapito, I will briefly describe the two celebrations coinciding with the beginning and end of the annual agricultural cycle in which the cross plays an important role: 3 May and the festivities for Saint Michael the Archangel at the end of September.

Celebrations for the Sacred Cross during the Month of May

The Day of the Sacred Cross, on 3 May, begins a cycle of celebrations for crosses in homes, in chapels, on hills, and at roadside shrines throughout the month in rural communities and urban neighborhoods. On the night of 2 May, the cycle is initiated with velaciones (nightlong vigil characteristic of Otomi celebrations with clear connotations of being a wake for the dead) in many chapels, including the chapel at Calderon Pass. During these nightlong vigils, members of different communities arrive in groups to honor the cross, carrying their own images, crosses, and offerings such as flowers and candles. Upon their arrival, they are received by the individuals in charge of the celebration, and together they enter the chapel accompanied by the clanging of the chapel bell to be blessed (or more accurately, "cleansed," for the ritual is called limpia) by their spiritual leaders and to make their offerings of candles and flowers. Because people travel from other communities, they come prepared to spend the night, and usually food, coffee, and liquor are offered. During the night, copal (a native incense made from pine resin) is burned, and the people sing hymns calling on the four winds, four cardinal directions, and the animas, or souls, of the ancestors to protect and bless them, accompanied by musicians who play mandolin-like instruments made out of armadillo shells (called conchas).5

Because the cult has been relatively isolated and because of the strong magical and shamanic elements involved, outsiders, including other peasants in the township who do not participate in the cult itself, frequently believe the participants are witches and should be avoided. Individuals who practice black magic also consider the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass as their principal source of supernatural energy, but those who actively participate in the cult rarely claim to do harm to others. In fact, it is considered to be very harmful if such people participate in the rituals and ceremonies because the celebrations, particularly the ones in September, emphasize reconciliation and the forgiveness of offenses rather than vengeance.

Chinampa

This image of Aztec agriculture, depicts cultivating of chinapa, or maguey plants, still in use Mexico's finest tequila's and mescals.

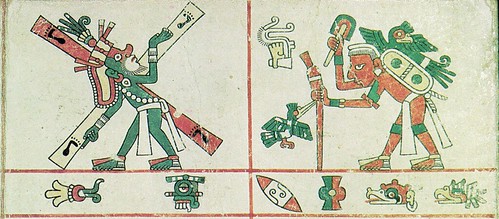

Codex Borbonicus, codex2

An excerpt from a scene depicting the 11th "week" of 13 days and nights ruled by the deity Patecatl, who was associated with pulque, a fermented maguey beverage

Date: The original Codex Borbonicus c. 1507, before the Spanish Conquest of Mexico, 1518-1521; a few scholars suggest it may have been created between 1522-1540, just after the Conquest of Mexico.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)