May 29, 2005

The web-site: "Great Masters of Mexican Folk Art," From the Collection of Fomento Cultural Banamex

Excellent web site, with a limited number of artists that respresent the vast number of working artists who continue to fuse the traditional with contemporary life, as it has always done. Art for indigenous artists is part of the ever-changing timeless present.

May 26, 2005

The Labyrinth of Solitutde, Octavio Paz

"All of us, at some moment, have had a vision of our existence a something unique, untransferable and very precious. This revelation almost always takes place during adolescence. Self-discovery is above all the realization that we are alone: it is the opening of an impalpable, transparent wall -- that of our consciousness -- between the world and ourselves. It is true that we sense our aloneness almost as soon as we are born, but children and adults can transcend their solitude and forget themselves in games and work. The adolescent, however vacillates between infancy and youth, halting for a moment before the infinite richness of the world. He is astonished at the fact of his being, and this astonishment leads to reflection: as he leans over the river of his consciousness, he asks himself if the face that appears there, disfigured by the water, is his own. The singularity of his being, which is pure sensation in children, becomes a problem and a question."

May 25, 2005

Portals to the World: Library of Congress Subject Experts on mExico

Every conceivable link about research on Mexico. Amazing.

May 24, 2005

The Mexican Cultural Institute of New York

Interesting site promoting the Mexican Arts.

Their mission statement is to "promote cultural expressions, art, education, science, technology and research of Mexico, as well as to foster the presence of the most innovative and contemporary cultural output from Mexico in New York and the United States in general."

Their mission statement is to "promote cultural expressions, art, education, science, technology and research of Mexico, as well as to foster the presence of the most innovative and contemporary cultural output from Mexico in New York and the United States in general."

Mexico Now, a Month-Long Festival to Celebrate Mexico’s Thriving Contemporary Arts Scene

From November 1st to 28, Mexico Now will flood leading arts venues in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens with the works and performances of nearly 100 of Mexico’s most renowned contemporary artists will participate in concerts, dance performances, exhibits and film screenings. For event information visit: www.mexiconowfestival.org

The Aztec Empire, Guggenheim Exhibition

The The most comprehensive survey of art and culture of the Aztecs ever assembled outside Mexico. More than 450 works drawn from major collections in the United States and Mexico, including many important works never before seen outside of Mexico, are featured in The Aztec Empire Exhibit.

may celebration of the santa cruz de calledron

Photos of the celebration of Sant Cruz in San Miguel.

Celebration of the Santa Cruz

Otomi rituals and celebrations: Crosses, Ancestors, and Resurrection

Journal of American Folklore, Fall 2000 by Correa, Phyllis M

...At the time of the Spanish conquest, a separate ethnic and linguistic group from the Nahuatl (of which the Aztecs were members), the Otomi, with a reputation for military prowess and acculturated into the general Mesoamerican cultural pattern of high civilization, occupied the northern and eastern border zones of the Aztec and Tarascan Empires. As subjects of these empires, the Otomi acted as protectors of the borders against incursions by the nomadic groups generically called Chichimecs to the north and east and also appear to have interacted with them for trade purposes as well. The area between the two Sierra Madre mountain ranges north of the Mesoamerican cultural area was mainly occupied by those nomadic groups and was called the Gran Chichimeca (Great Chichimec Region) by the Spanish. The location where San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende) was established held strategic importance for the expansion of Spanish domination into an area not under the control of the prehispanic empires and also played an important economic and commercial role throughout the colonial period as a supply center for the gold and silver mines discovered in Guanajuato and Zacatecas to the north.

Otomies from Jilotepec Province, to the north of the Valley of Mexico, were active participants in the conquest of both Queretaro and Guanajuato during the early colonial period as allies of the Spanish and provided the earliest colonizers, who, together with groups of pacified Chichimecs, created a network integrating local communities into a broader social, economic, and political system that also served as the basis for a regional identity. Today, this network is maintained primarily through the reciprocal participation in religious celebrations throughout the area and the existence of a hierarchy of groups and individuals involved in the organization of these celebrations. The Laja River, a tributary of the Lerma-Santiago River system, lies four kilometers to the west of San Miguel de Allende and was the main zone of Otomi occupation, including several traditional barrios of the city itself In recent decades, the use of the Otomi language has virtually disappeared in Guanajuato, and it is virtually impossible to distinguish the Otomi from mestizo peasants and residents of marginal urban neighborhoods who generally do not participate in the religious complex.1

The rituals and ceremonies described in this article that form part of the Otomi religious complex took place during Holy Week in the family chapel of Don Agapito R., a former resident of the ranch of Tirado, which was inundated by a large dam built in the late 1960s. When forced to leave, Don Agapito, who is now close to 90 years old, purchased a large lot on the outskirts of town near the railroad station where he and his extended family reside. A small chapel was built to house religious objects he recovered from the two chapels of Tirado consisting primarily of a number of crosses; statues of Saints Michael and James, to whom the chapels of the ranch were dedicated; and several retablos of saints. Retablos are religious pictures of saints drawn on tin or scenes describing the miraculous deed of a saint to whom the petitioner turned in a time of need. The second type can be found on the walls of many churches and shrines offered as an expression of gratitude to a specific image.

Crosses, with distinct characteristics and of differing types, are central to Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the cross as a symbol of the four winds and four cardinal directions, as well as the veneration of the ancestors and their relationship to fire, the sun, military conquest, and sacrifice. Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint James, the patron saint of the Spanish reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, are both important figures within the Otomi religious configuration as divine warriors. Of the retablos in Don Agapito's chapel, one depicting San Isidro Labrador, called the demandita (literally, the "little petition"), is the most important. San Isidro, whose feast day is 15 May, was celebrated elaborately in the former community of Tirado and is the principal patron saint of numerous rural communities around San Miguel.2 Apparently a large oil painting of this saint was taken by another member of the community and is housed in their family chapel.

Don Agapito and his family perform rituals and celebrations on various occasions throughout the year, and in September, during the celebrations to Saint Michael the Archangel, the patron saint of the city, they continue to make the offering for the ancestors in the name of the community of Tirado. According to Don Agapito, as long as he lives, he will maintain these traditions and hopefully his family will continue them. To quote him, "Everything changes, but the traditions go on. If one person is missing, there is another 'to pick up the word.'" This statement reflects the central thesis of this article: that popular religion in Mexico, while retaining a central core of elements and beliefs that forms the basis for its ideology and cosmovision, is not conservative or static but, rather, adapts in response to changing circumstances and is continually being created and re-created as traditions are transmitted both orally and through active participation in rituals and ceremonies to new generations. Furthermore, this central core of elements and beliefs is more closely related to a prehispanic configuration, in this case Otomi, and Catholic elements adopted or appropriated have been reworked to conform to that general conceptualization. The central issues to be examined revolve around questions of continuity (what remains stable and why) and change, which in this particular instance was the dissolution of a rural community as the result of a state project (the building of a dam). It is hoped that this example can shed some light on how external pressures can disrupt the community-wide organization of religious celebrations and yet, on an individual and familial level, can be maintained and transmitted. To understand the context of Otomi popular religious traditions in the zone within which the specific rituals analyzed are performed, it is first necessary to have a general overview of the ceremonies, symbolic elements, and cosmology as manifested in this area of central Mexico.

The Sacred Cross of Calder6n Pass

The primary focal point of popular religion among the Otomi who inhabit the communities along the Laja River in the State of Guanajuato, including the city of San Miguel de Allende, is the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass. This particular cross integrates a number of traditional urban neighborhoods and rural communities both within the township and throughout much of the central highlands, primarily the Bajio region to the south,3 in a network based on the worship of crosses, other religious saints and images, and sacred places.

According to the story transmitted from generation to generation, on 14 September 1531, non-Christianized Chichimecs confronted Christianized Otomi and Chichimec captains in an streambed near Calderon Pass in a bloody battle that lasted 15 days and nights until suddenly it grew dark and a shining cross appeared in the sky. Upon seeing this supernatural sign, the non-Christianized natives stopped fighting and cried out, "El es Dios" [He is God]. The supernatural appearance of the cross meant that they should surrender and accept the Catholic faith, making peace with their native brothers who had fought against them. A cross was carved out of stone and taken to the high part of the pass where a chapel was built.

This stone cross is about four feet tall and rests on a small pedestal. It has been covered with a thin layer of tin that is painted a dark burnished brown and covered with diverse figures representing the passion and death of Christ, two human figures who look like native dancers, the sun and moon at each point of the horizontal axis, a bloodied dagger at the base, the sacred heart of Christ, and a pair of severed feet and severed hands with the palms showing. Despite their relationship to Christian beliefs (the hands and feet of Christ had nails driven in them when he was crucified, and his heart was pierced to be sure he was dead), in prehispanic times the feet and hands of sacrificial victims were sent to the principal lords, while the head and heart could only be eaten by the high priests or emperor (Gonzalez Torres 1994:294). On a short crosspiece at the very top of the cross is a mirror encrusted in the stone with the letters "I N R I" The cross itself is topped off with a small metal crown. A very important feature of the cross is the tiny head of Christ carved from wood and inserted in a hollow precisely at the intersection of the two axes, making it look as though the figure of Christ is completely enveloped by the cross. This style of the Christ figure being inserted within the material of the cross, whether it is made of wood or stone, is relatively common in the areas inhabited by the Otomi. The wooden crosses of this type are also covered almost completely with mirrors painted with the figures of the passion of Christ and, in some cases, also showing the hands, feet, and heart of Christ.

Calderon Pass is sacred not only because it overlooks a river valley to the north and another to the south, a location that forms a natural opening and is also a sort of natural crossroads, but also because of its location near where the battle of 1531 took place. Many important locations in Otomi sacred geography have been blessed by blood being shed in a violent way. Energy emanating from the souls of the dead creates an opening to communicate with supernatural beings and provides the power used by practitioners to perform magic. These locations as well as the tops of mountains, crossroads, caves, and points of the five cardinal directions are all called puertos, which literally translated means "passages" or "openings."4

To better understand the general complex of Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the worship of the Sacred Cross of Calderon and the rituals described in the family chapel of Don Agapito, I will briefly describe the two celebrations coinciding with the beginning and end of the annual agricultural cycle in which the cross plays an important role: 3 May and the festivities for Saint Michael the Archangel at the end of September.

Celebrations for the Sacred Cross during the Month of May

The Day of the Sacred Cross, on 3 May, begins a cycle of celebrations for crosses in homes, in chapels, on hills, and at roadside shrines throughout the month in rural communities and urban neighborhoods. On the night of 2 May, the cycle is initiated with velaciones (nightlong vigil characteristic of Otomi celebrations with clear connotations of being a wake for the dead) in many chapels, including the chapel at Calderon Pass. During these nightlong vigils, members of different communities arrive in groups to honor the cross, carrying their own images, crosses, and offerings such as flowers and candles. Upon their arrival, they are received by the individuals in charge of the celebration, and together they enter the chapel accompanied by the clanging of the chapel bell to be blessed (or more accurately, "cleansed," for the ritual is called limpia) by their spiritual leaders and to make their offerings of candles and flowers. Because people travel from other communities, they come prepared to spend the night, and usually food, coffee, and liquor are offered. During the night, copal (a native incense made from pine resin) is burned, and the people sing hymns calling on the four winds, four cardinal directions, and the animas, or souls, of the ancestors to protect and bless them, accompanied by musicians who play mandolin-like instruments made out of armadillo shells (called conchas).5

Because the cult has been relatively isolated and because of the strong magical and shamanic elements involved, outsiders, including other peasants in the township who do not participate in the cult itself, frequently believe the participants are witches and should be avoided. Individuals who practice black magic also consider the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass as their principal source of supernatural energy, but those who actively participate in the cult rarely claim to do harm to others. In fact, it is considered to be very harmful if such people participate in the rituals and ceremonies because the celebrations, particularly the ones in September, emphasize reconciliation and the forgiveness of offenses rather than vengeance.

Journal of American Folklore, Fall 2000 by Correa, Phyllis M

...At the time of the Spanish conquest, a separate ethnic and linguistic group from the Nahuatl (of which the Aztecs were members), the Otomi, with a reputation for military prowess and acculturated into the general Mesoamerican cultural pattern of high civilization, occupied the northern and eastern border zones of the Aztec and Tarascan Empires. As subjects of these empires, the Otomi acted as protectors of the borders against incursions by the nomadic groups generically called Chichimecs to the north and east and also appear to have interacted with them for trade purposes as well. The area between the two Sierra Madre mountain ranges north of the Mesoamerican cultural area was mainly occupied by those nomadic groups and was called the Gran Chichimeca (Great Chichimec Region) by the Spanish. The location where San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende) was established held strategic importance for the expansion of Spanish domination into an area not under the control of the prehispanic empires and also played an important economic and commercial role throughout the colonial period as a supply center for the gold and silver mines discovered in Guanajuato and Zacatecas to the north.

Otomies from Jilotepec Province, to the north of the Valley of Mexico, were active participants in the conquest of both Queretaro and Guanajuato during the early colonial period as allies of the Spanish and provided the earliest colonizers, who, together with groups of pacified Chichimecs, created a network integrating local communities into a broader social, economic, and political system that also served as the basis for a regional identity. Today, this network is maintained primarily through the reciprocal participation in religious celebrations throughout the area and the existence of a hierarchy of groups and individuals involved in the organization of these celebrations. The Laja River, a tributary of the Lerma-Santiago River system, lies four kilometers to the west of San Miguel de Allende and was the main zone of Otomi occupation, including several traditional barrios of the city itself In recent decades, the use of the Otomi language has virtually disappeared in Guanajuato, and it is virtually impossible to distinguish the Otomi from mestizo peasants and residents of marginal urban neighborhoods who generally do not participate in the religious complex.1

The rituals and ceremonies described in this article that form part of the Otomi religious complex took place during Holy Week in the family chapel of Don Agapito R., a former resident of the ranch of Tirado, which was inundated by a large dam built in the late 1960s. When forced to leave, Don Agapito, who is now close to 90 years old, purchased a large lot on the outskirts of town near the railroad station where he and his extended family reside. A small chapel was built to house religious objects he recovered from the two chapels of Tirado consisting primarily of a number of crosses; statues of Saints Michael and James, to whom the chapels of the ranch were dedicated; and several retablos of saints. Retablos are religious pictures of saints drawn on tin or scenes describing the miraculous deed of a saint to whom the petitioner turned in a time of need. The second type can be found on the walls of many churches and shrines offered as an expression of gratitude to a specific image.

Crosses, with distinct characteristics and of differing types, are central to Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the cross as a symbol of the four winds and four cardinal directions, as well as the veneration of the ancestors and their relationship to fire, the sun, military conquest, and sacrifice. Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint James, the patron saint of the Spanish reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, are both important figures within the Otomi religious configuration as divine warriors. Of the retablos in Don Agapito's chapel, one depicting San Isidro Labrador, called the demandita (literally, the "little petition"), is the most important. San Isidro, whose feast day is 15 May, was celebrated elaborately in the former community of Tirado and is the principal patron saint of numerous rural communities around San Miguel.2 Apparently a large oil painting of this saint was taken by another member of the community and is housed in their family chapel.

Don Agapito and his family perform rituals and celebrations on various occasions throughout the year, and in September, during the celebrations to Saint Michael the Archangel, the patron saint of the city, they continue to make the offering for the ancestors in the name of the community of Tirado. According to Don Agapito, as long as he lives, he will maintain these traditions and hopefully his family will continue them. To quote him, "Everything changes, but the traditions go on. If one person is missing, there is another 'to pick up the word.'" This statement reflects the central thesis of this article: that popular religion in Mexico, while retaining a central core of elements and beliefs that forms the basis for its ideology and cosmovision, is not conservative or static but, rather, adapts in response to changing circumstances and is continually being created and re-created as traditions are transmitted both orally and through active participation in rituals and ceremonies to new generations. Furthermore, this central core of elements and beliefs is more closely related to a prehispanic configuration, in this case Otomi, and Catholic elements adopted or appropriated have been reworked to conform to that general conceptualization. The central issues to be examined revolve around questions of continuity (what remains stable and why) and change, which in this particular instance was the dissolution of a rural community as the result of a state project (the building of a dam). It is hoped that this example can shed some light on how external pressures can disrupt the community-wide organization of religious celebrations and yet, on an individual and familial level, can be maintained and transmitted. To understand the context of Otomi popular religious traditions in the zone within which the specific rituals analyzed are performed, it is first necessary to have a general overview of the ceremonies, symbolic elements, and cosmology as manifested in this area of central Mexico.

The Sacred Cross of Calder6n Pass

The primary focal point of popular religion among the Otomi who inhabit the communities along the Laja River in the State of Guanajuato, including the city of San Miguel de Allende, is the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass. This particular cross integrates a number of traditional urban neighborhoods and rural communities both within the township and throughout much of the central highlands, primarily the Bajio region to the south,3 in a network based on the worship of crosses, other religious saints and images, and sacred places.

According to the story transmitted from generation to generation, on 14 September 1531, non-Christianized Chichimecs confronted Christianized Otomi and Chichimec captains in an streambed near Calderon Pass in a bloody battle that lasted 15 days and nights until suddenly it grew dark and a shining cross appeared in the sky. Upon seeing this supernatural sign, the non-Christianized natives stopped fighting and cried out, "El es Dios" [He is God]. The supernatural appearance of the cross meant that they should surrender and accept the Catholic faith, making peace with their native brothers who had fought against them. A cross was carved out of stone and taken to the high part of the pass where a chapel was built.

This stone cross is about four feet tall and rests on a small pedestal. It has been covered with a thin layer of tin that is painted a dark burnished brown and covered with diverse figures representing the passion and death of Christ, two human figures who look like native dancers, the sun and moon at each point of the horizontal axis, a bloodied dagger at the base, the sacred heart of Christ, and a pair of severed feet and severed hands with the palms showing. Despite their relationship to Christian beliefs (the hands and feet of Christ had nails driven in them when he was crucified, and his heart was pierced to be sure he was dead), in prehispanic times the feet and hands of sacrificial victims were sent to the principal lords, while the head and heart could only be eaten by the high priests or emperor (Gonzalez Torres 1994:294). On a short crosspiece at the very top of the cross is a mirror encrusted in the stone with the letters "I N R I" The cross itself is topped off with a small metal crown. A very important feature of the cross is the tiny head of Christ carved from wood and inserted in a hollow precisely at the intersection of the two axes, making it look as though the figure of Christ is completely enveloped by the cross. This style of the Christ figure being inserted within the material of the cross, whether it is made of wood or stone, is relatively common in the areas inhabited by the Otomi. The wooden crosses of this type are also covered almost completely with mirrors painted with the figures of the passion of Christ and, in some cases, also showing the hands, feet, and heart of Christ.

Calderon Pass is sacred not only because it overlooks a river valley to the north and another to the south, a location that forms a natural opening and is also a sort of natural crossroads, but also because of its location near where the battle of 1531 took place. Many important locations in Otomi sacred geography have been blessed by blood being shed in a violent way. Energy emanating from the souls of the dead creates an opening to communicate with supernatural beings and provides the power used by practitioners to perform magic. These locations as well as the tops of mountains, crossroads, caves, and points of the five cardinal directions are all called puertos, which literally translated means "passages" or "openings."4

To better understand the general complex of Otomi religious traditions, which revolve around the worship of the Sacred Cross of Calderon and the rituals described in the family chapel of Don Agapito, I will briefly describe the two celebrations coinciding with the beginning and end of the annual agricultural cycle in which the cross plays an important role: 3 May and the festivities for Saint Michael the Archangel at the end of September.

Celebrations for the Sacred Cross during the Month of May

The Day of the Sacred Cross, on 3 May, begins a cycle of celebrations for crosses in homes, in chapels, on hills, and at roadside shrines throughout the month in rural communities and urban neighborhoods. On the night of 2 May, the cycle is initiated with velaciones (nightlong vigil characteristic of Otomi celebrations with clear connotations of being a wake for the dead) in many chapels, including the chapel at Calderon Pass. During these nightlong vigils, members of different communities arrive in groups to honor the cross, carrying their own images, crosses, and offerings such as flowers and candles. Upon their arrival, they are received by the individuals in charge of the celebration, and together they enter the chapel accompanied by the clanging of the chapel bell to be blessed (or more accurately, "cleansed," for the ritual is called limpia) by their spiritual leaders and to make their offerings of candles and flowers. Because people travel from other communities, they come prepared to spend the night, and usually food, coffee, and liquor are offered. During the night, copal (a native incense made from pine resin) is burned, and the people sing hymns calling on the four winds, four cardinal directions, and the animas, or souls, of the ancestors to protect and bless them, accompanied by musicians who play mandolin-like instruments made out of armadillo shells (called conchas).5

Because the cult has been relatively isolated and because of the strong magical and shamanic elements involved, outsiders, including other peasants in the township who do not participate in the cult itself, frequently believe the participants are witches and should be avoided. Individuals who practice black magic also consider the Sacred Cross of Calderon Pass as their principal source of supernatural energy, but those who actively participate in the cult rarely claim to do harm to others. In fact, it is considered to be very harmful if such people participate in the rituals and ceremonies because the celebrations, particularly the ones in September, emphasize reconciliation and the forgiveness of offenses rather than vengeance.

Chinampa

This image of Aztec agriculture, depicts cultivating of chinapa, or maguey plants, still in use Mexico's finest tequila's and mescals.

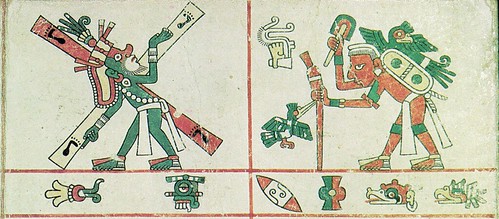

Codex Borbonicus, codex2

An excerpt from a scene depicting the 11th "week" of 13 days and nights ruled by the deity Patecatl, who was associated with pulque, a fermented maguey beverage

Date: The original Codex Borbonicus c. 1507, before the Spanish Conquest of Mexico, 1518-1521; a few scholars suggest it may have been created between 1522-1540, just after the Conquest of Mexico.

May 21, 2005

The City, the state, their history, and story.

LOS ANTEPASADOS INDÍGENAS DE LOS GUANAJUATENSES:

A Look into Guanajuato's Past

By John P. Schmal

For the better part of a hundred years, thousands of people have emigrated from the central Mexican state of Guanajuato to the United States. A hundred years ago, fifty years ago - and today - Guanajuatenses have represented a significant portion of all Mexican immigrants to Los Estados Unidos. It can thus be stated that millions of Americans look to the state of Guanajuato as their "madre patria" and that we all know people whose roots are nested in this beautiful state. As a matter of fact, a paternal great-grandmother of my nieces and nephews came from Valle de Santiago in the state of Guanajuato.

But what do most Guanajuato-Americanos know of their ancestral homeland? The Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato is a landlocked state in the center of the Mexican Republic. It shares borders with San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas on the north, with Querétaro on the east, the state of México on the southeast, Jalisco on the west, and Michoacán on the south.

Guanajuato is a relatively small state - twenty-second in terms of size among the Republic's thirty-one states - with a surface area of 30,768 square kilometers of territory, giving it 1.6% of the national territory. Politically, it is divided into 46 municipios. The capital of Guanajuato is the city of Guanajuato, founded in the middle of the Sixteenth Century after Spanish entrepreneurs found rich veins of silver in the mountains surrounding the city.

But there was a large group of people who inhabited Guanajuato long before Spanish businessmen arrived with their Náhuatl-speaking allies from the south of Mexico. When the strangers first entered this land, they made no effort to distinguish between the various cultures living in Guanajuato. Instead, they applied the term Chichimeca to these aboriginal peoples. Utilizing the Náhuatl terms for dog (chichi) and rope (mecatl), the Aztec Indians had regarded their northern neighbors - the Chichimecas - as being "of dog lineage." (The implication of the term rope was a reference to "following the dog," hence a descendant of the dog).

But the Chichimecas were also given other labels, such as "perros altaneros" (arrogant dogs), or "chupadores de sangre" (blood-suckers). The late great Dr. Philip Wayne Powell - whose "Soldiers, Indians, and Silver: North America's First Frontier War" is the definitive source of information relating to the Chichimeca Indians - referred to Chichimeca as "an all-inclusive epithet" that had "a spiteful connotation."

But it is important to mention that the word Chichimeca was just an umbrella term that the Spaniards used to describe most of the indigenous groups scattered through large parts of Guanajuato, Jalisco, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Aguascalientes, and Durango. The Chichimeca peoples were actually composed of several distinct cultural and linguistic groups inhabiting this area.

Because these indigenous groups are, in fact, the ancestors of the present-day Guanajuatenses and their Mexican-American cousins, it is worth exploring them as the individual cultures they once were. The group that occupied the western end of present-day Guanajuato was known as the Guachichiles.

The Guachichiles, of all the Chichimeca Indians, occupied the most extensive territory stretching north to Saltillo in Coahuila and to the northern corners of Michoacán in the south. Considered both warlike and brave, the Guachichiles roamed through a large section of the Zacatecas, as well as portions of San Luis Potosí, Guanajuato and northeastern Jalisco. Some bands of Guachichile Indians reached as far south as the present-day boundary of Guanajuato and Michoacán.

The name "Guachichile" that the Mexicans gave to these Indians meant "heads painted of red," a reference to the red dye that they used to pain their bodies, faces and hair. According to John R. Swanton, the author of "The Indian Tribes of North America," (Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 145-1953) classified the Guachichile tribes as part of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family. This would make them linguistic cousins to the Aztecs.

The Guamares - another Chichimeca group - inhabited a large section of Guanajuato. They were centered in the Guanajuato Sierras, but had some bands that ranged as far east as the state of Querétaro. The author Seventeenth-Century author Gonzalo de las Casas called the Guamares "the bravest, most warlike, treacherous and destructive of all the Chichimecas, and the most astute (dispuesta)."

One of the few scholars to study the lifestyle of the Guachichiles, Guamares, and other Chichimecas in detail was the archaeologist, Dr. Paul Kirchhoff. His work, "The Hunting-Gathering People of North Mexico," is one of the few reference works available that describes the social and political organization of both the Guamares and Guachichile (See "Sources" below for the citation).

The semi nomadic Pames constituted a very divergent branch of the extensive Oto-Manguean linguistic family. They were located mainly in the north central and eastern Guanajuato, southeastern San Luis Potosí, and also in adjacent areas of Tamaulipas and Querétaro. To this day, the Pames refer to themselves as "Xi'úi," which means indigenous. This term is used to refer to any person not of mestizo descent. They use the word "Pame" to refer to themselves only when they are speaking Spanish. But in their religion, this word has a contemptuous meaning and they try to avoid using it.

From 1550 to 1590, the Guachichiles, Guamares and Pames waged a fierce guerilla war against the Spaniards and Christian Indians. The Spaniards and their allies had entered Guanajuato and Zacatecas to exploit their rich mineral resources. But to the Chichimeca groups, this land was home, so they regarded these intrusions as a disruption of their sovereign rights. Dr. Powell's work (mentioned above) discusses this war in great detail. And the people of Guanajuato can be proud of the fact that their ancestors had to bribed into making peace.

Unable to defeat the Chichimecas militarily in many parts of the war zone, the Spaniards offered goods and opportunities as an incentive for the Guachichiles and Guamares to make peace. Many of the Chichimecas had been nomadic (or semi-nomadic) and had not possessed most of the luxury items that the Spaniards had (i.e., warm clothes, agricultural tools and supplies, horses, and beef). Those who made peace were given agricultural implements and permitted to settle down to a peaceful agricultural existence. In many cases, Christian Indians from the south were settled among them to help them adapt to their new existence.

The Otomíes were another Chichimeca tribe, occupying the greater part of Querétaro and smaller parts of Guanajuato, the northwestern portion of Hidalgo and parts of the state of México. The Otomíes are one of the largest and oldest indigenous groups in Mexico, and include many different groups, including the Mazahua, Matlatzinca, Ocuiltec, the Pame and the Chichimec Jonaz.

Many of the Otomíes aligned themselves with the Spaniards during the Chichimeca War. As a result, wrote Dr. Powell, Otomí settlers were "issued a grant of privileges" and were "supplied with tools for breaking land." For their allegiance, they were exempted from tribute and given a certain amount of autonomy in their towns. The Otomí are described in great detail by the U.C. Davis graduate student, Kerin Gould, in her work, "The Otomí: Complex History, Adaptable Culture, Common Heritage" at the following website:

http://home.earthlink.net/~kering/history.html

In pre-Hispanic times, the Purépecha Indians - also referred to as the Tarascan Indians - occupied most of the state of Michoacán, but they also occupied some of the lower valleys of both Guanajuato and Jalisco. Celaya, Acámbaro, and Yurirapúndaro were all in Purépecha territory.

It is believed that the Spanish explorer Cristóbal de Olid, upon arriving in the Kingdom of the Purépecha in present-day Michoacán, probably explored some parts of Guanajuato in the early 1520s. Then in 1529-1530, the forces of the ruthless Nuño de Guzmán ravaged through most of Michoacán and some parts of Guanajuato with an army of 500 Spanish soldiers and more than 10,000 Indian warriors.

In 1552 Captain Juan de Jaso discovered the mining veins of the present-day city of Guanajuato. This picturesque city - founded a few years later - nestles snugly into a valley of the mountains of the Sierra de Guanajuato. The indigenous tribes of the area made note of the numerous frogs in the area and referred to it as Quanax-juato - "Place of Frogs," the sound of which the Spanish would translate to "Guanajuato."

The Valenciana silver mine located near the City of Guanajuato was one of the richest silver finds in all history. In the Eighteenth century this mine alone accounted for 60% of the world's total silver production. For this reason, Guanajuato flourished as the silver mining capital of the world for three centuries, producing nearly a third of the world's silver during this time.

After the Chichimeca Indians were persuaded to settle down in the late Sixteenth Century, Guanajuato experienced a high degree of mestizaje. This would be due in great part to the huge influx of a very diverse group of people from many parts of the Spanish colony of Mexico. The influx of more established and refined Indian cultural groups combined with the establishment of the Spanish language and Christian religion as the dominant cultural practice. And the result was a high degree of assimilation, in which most traces of the old cultures were lost.

In modern times, Guanajuato has had a very small population of people speaking indigenous languages. Although many of the Guanajuatenses are believed to be descended from the indigenous inhabitants of their state, the cultures and languages of their ancestors - for the most part - have not been handed down to the descendants. In the 1895 census, only 9,607 persons aged five or more spoke indigenous languages. This figure rose to 14,586 in 1910, but dropped to only 305 in the 1930 census, in large part because of the ravages of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), which took the life of one in eight Mexican citizens.

As a matter of fact, Guanajuato's total population fell from an all-time high in the 1910 census (1,081,651 persons) to a Twentieth Century low of 860,364 in the 1921 census. But the 1921 Mexican census gives us a very interesting view of the widespread mestizaje of Guanajuato's modern population. In this census, residents of each state were asked to classify themselves in several categories, including "indígena pura" (pure indigenous), "indígena mezclada con blanca" (indigenous mixed with white), and "blanca" (white). Out of a total district population of 860,364 people, only 25,458 individuals (or 2.96%) claimed to be of pure indigenous background. A much larger number - 828,724, or 96.33% - classified themselves as being mixed, while a mere 4,687 individuals (0.5%) classified themselves as white.

From the latter half of the Twentieth Century into the present century, the population of indigenous speakers has remained fairly small. When the 1970 census was tallied, Guanajuato boasted a mere 2,272 indigenous speakers five years of age and over. The Otomí speakers made up the most significant number (866), followed by the Purépecha (181) and Náhuatl (151). The Chichimeca-Jonaz language, a rare language spoken in only in Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí, was not tallied individually in the 1970 census, but was probably among the 790 persons listed under "otras lenguas Indígenas."

According to the most recent census (2000), the population of persons five years and more who spoke indigenous languages in Guanajuato amounted to only 10,689 individuals, or 0.26% of the total state population. These individuals spoke a wide range of languages, many of which are transplants from other parts of the Mexican Republic. The largest indigenous groups represented in the state were: Chichimeca Jonaz (1,433), Otomí (1,019), Náhuatl (919), Mazahua (626), Purépecha (414), Mixteco (225), and Zapoteco (214).

Today, the Chichimeca-Jonaz language is found only in the states of San Luis Potosí and Guanajuato. Chichimeca Jonaz is classified as a member of the Oto-Manguean language family and is divided into two major dialects: the Pame dialect, which is used in San Luis Potosí, and the Jonaz dialect used in Guanajuato. With a total of 1,433 Chichimeca-Jonaz speakers living in the state of Guanajuato in 2000, it is interesting to note that the great majority - 1,405 persons five years of age or more - actually lived in the municipio of San Luis de la Paz.

All of the other languages spoken in Guanajuato are not well represented. In fact, all of these languages are spoken by many more people living in other Mexican states, some of these states being adjacent to Guanajuato. The Mixteco and Zapoteco are indigenous to the state of Oaxaca, while the other languages have cultural centers in Querétaro, Puebla and Mexico.

The people of Guanajuato are the living representation of their indigenous ancestors. While most of the languages and cultures have disappeared or been absorbed into the central Hispanic culture, the people of Guanajuato have inherited the genetic legacy of the original Indian people. In this respect at least, the indigenous people of pre-Hispanic Guanajuato will endure forever.

Copyright © 2004 by John P. Schmal. All Rights Reserved. Read more articles by John Schmal. Additional articles on The Aztec Empire, the History of Mexico, and Mexican Traditions are available at http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/guanajuato.html

A Look into Guanajuato's Past

By John P. Schmal

For the better part of a hundred years, thousands of people have emigrated from the central Mexican state of Guanajuato to the United States. A hundred years ago, fifty years ago - and today - Guanajuatenses have represented a significant portion of all Mexican immigrants to Los Estados Unidos. It can thus be stated that millions of Americans look to the state of Guanajuato as their "madre patria" and that we all know people whose roots are nested in this beautiful state. As a matter of fact, a paternal great-grandmother of my nieces and nephews came from Valle de Santiago in the state of Guanajuato.

But what do most Guanajuato-Americanos know of their ancestral homeland? The Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato is a landlocked state in the center of the Mexican Republic. It shares borders with San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas on the north, with Querétaro on the east, the state of México on the southeast, Jalisco on the west, and Michoacán on the south.

Guanajuato is a relatively small state - twenty-second in terms of size among the Republic's thirty-one states - with a surface area of 30,768 square kilometers of territory, giving it 1.6% of the national territory. Politically, it is divided into 46 municipios. The capital of Guanajuato is the city of Guanajuato, founded in the middle of the Sixteenth Century after Spanish entrepreneurs found rich veins of silver in the mountains surrounding the city.

But there was a large group of people who inhabited Guanajuato long before Spanish businessmen arrived with their Náhuatl-speaking allies from the south of Mexico. When the strangers first entered this land, they made no effort to distinguish between the various cultures living in Guanajuato. Instead, they applied the term Chichimeca to these aboriginal peoples. Utilizing the Náhuatl terms for dog (chichi) and rope (mecatl), the Aztec Indians had regarded their northern neighbors - the Chichimecas - as being "of dog lineage." (The implication of the term rope was a reference to "following the dog," hence a descendant of the dog).

But the Chichimecas were also given other labels, such as "perros altaneros" (arrogant dogs), or "chupadores de sangre" (blood-suckers). The late great Dr. Philip Wayne Powell - whose "Soldiers, Indians, and Silver: North America's First Frontier War" is the definitive source of information relating to the Chichimeca Indians - referred to Chichimeca as "an all-inclusive epithet" that had "a spiteful connotation."

But it is important to mention that the word Chichimeca was just an umbrella term that the Spaniards used to describe most of the indigenous groups scattered through large parts of Guanajuato, Jalisco, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Aguascalientes, and Durango. The Chichimeca peoples were actually composed of several distinct cultural and linguistic groups inhabiting this area.

Because these indigenous groups are, in fact, the ancestors of the present-day Guanajuatenses and their Mexican-American cousins, it is worth exploring them as the individual cultures they once were. The group that occupied the western end of present-day Guanajuato was known as the Guachichiles.

The Guachichiles, of all the Chichimeca Indians, occupied the most extensive territory stretching north to Saltillo in Coahuila and to the northern corners of Michoacán in the south. Considered both warlike and brave, the Guachichiles roamed through a large section of the Zacatecas, as well as portions of San Luis Potosí, Guanajuato and northeastern Jalisco. Some bands of Guachichile Indians reached as far south as the present-day boundary of Guanajuato and Michoacán.

The name "Guachichile" that the Mexicans gave to these Indians meant "heads painted of red," a reference to the red dye that they used to pain their bodies, faces and hair. According to John R. Swanton, the author of "The Indian Tribes of North America," (Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 145-1953) classified the Guachichile tribes as part of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family. This would make them linguistic cousins to the Aztecs.

The Guamares - another Chichimeca group - inhabited a large section of Guanajuato. They were centered in the Guanajuato Sierras, but had some bands that ranged as far east as the state of Querétaro. The author Seventeenth-Century author Gonzalo de las Casas called the Guamares "the bravest, most warlike, treacherous and destructive of all the Chichimecas, and the most astute (dispuesta)."

One of the few scholars to study the lifestyle of the Guachichiles, Guamares, and other Chichimecas in detail was the archaeologist, Dr. Paul Kirchhoff. His work, "The Hunting-Gathering People of North Mexico," is one of the few reference works available that describes the social and political organization of both the Guamares and Guachichile (See "Sources" below for the citation).

The semi nomadic Pames constituted a very divergent branch of the extensive Oto-Manguean linguistic family. They were located mainly in the north central and eastern Guanajuato, southeastern San Luis Potosí, and also in adjacent areas of Tamaulipas and Querétaro. To this day, the Pames refer to themselves as "Xi'úi," which means indigenous. This term is used to refer to any person not of mestizo descent. They use the word "Pame" to refer to themselves only when they are speaking Spanish. But in their religion, this word has a contemptuous meaning and they try to avoid using it.

From 1550 to 1590, the Guachichiles, Guamares and Pames waged a fierce guerilla war against the Spaniards and Christian Indians. The Spaniards and their allies had entered Guanajuato and Zacatecas to exploit their rich mineral resources. But to the Chichimeca groups, this land was home, so they regarded these intrusions as a disruption of their sovereign rights. Dr. Powell's work (mentioned above) discusses this war in great detail. And the people of Guanajuato can be proud of the fact that their ancestors had to bribed into making peace.

Unable to defeat the Chichimecas militarily in many parts of the war zone, the Spaniards offered goods and opportunities as an incentive for the Guachichiles and Guamares to make peace. Many of the Chichimecas had been nomadic (or semi-nomadic) and had not possessed most of the luxury items that the Spaniards had (i.e., warm clothes, agricultural tools and supplies, horses, and beef). Those who made peace were given agricultural implements and permitted to settle down to a peaceful agricultural existence. In many cases, Christian Indians from the south were settled among them to help them adapt to their new existence.

The Otomíes were another Chichimeca tribe, occupying the greater part of Querétaro and smaller parts of Guanajuato, the northwestern portion of Hidalgo and parts of the state of México. The Otomíes are one of the largest and oldest indigenous groups in Mexico, and include many different groups, including the Mazahua, Matlatzinca, Ocuiltec, the Pame and the Chichimec Jonaz.

Many of the Otomíes aligned themselves with the Spaniards during the Chichimeca War. As a result, wrote Dr. Powell, Otomí settlers were "issued a grant of privileges" and were "supplied with tools for breaking land." For their allegiance, they were exempted from tribute and given a certain amount of autonomy in their towns. The Otomí are described in great detail by the U.C. Davis graduate student, Kerin Gould, in her work, "The Otomí: Complex History, Adaptable Culture, Common Heritage" at the following website:

http://home.earthlink.net/~kering/history.html

In pre-Hispanic times, the Purépecha Indians - also referred to as the Tarascan Indians - occupied most of the state of Michoacán, but they also occupied some of the lower valleys of both Guanajuato and Jalisco. Celaya, Acámbaro, and Yurirapúndaro were all in Purépecha territory.

It is believed that the Spanish explorer Cristóbal de Olid, upon arriving in the Kingdom of the Purépecha in present-day Michoacán, probably explored some parts of Guanajuato in the early 1520s. Then in 1529-1530, the forces of the ruthless Nuño de Guzmán ravaged through most of Michoacán and some parts of Guanajuato with an army of 500 Spanish soldiers and more than 10,000 Indian warriors.

In 1552 Captain Juan de Jaso discovered the mining veins of the present-day city of Guanajuato. This picturesque city - founded a few years later - nestles snugly into a valley of the mountains of the Sierra de Guanajuato. The indigenous tribes of the area made note of the numerous frogs in the area and referred to it as Quanax-juato - "Place of Frogs," the sound of which the Spanish would translate to "Guanajuato."

The Valenciana silver mine located near the City of Guanajuato was one of the richest silver finds in all history. In the Eighteenth century this mine alone accounted for 60% of the world's total silver production. For this reason, Guanajuato flourished as the silver mining capital of the world for three centuries, producing nearly a third of the world's silver during this time.

After the Chichimeca Indians were persuaded to settle down in the late Sixteenth Century, Guanajuato experienced a high degree of mestizaje. This would be due in great part to the huge influx of a very diverse group of people from many parts of the Spanish colony of Mexico. The influx of more established and refined Indian cultural groups combined with the establishment of the Spanish language and Christian religion as the dominant cultural practice. And the result was a high degree of assimilation, in which most traces of the old cultures were lost.

In modern times, Guanajuato has had a very small population of people speaking indigenous languages. Although many of the Guanajuatenses are believed to be descended from the indigenous inhabitants of their state, the cultures and languages of their ancestors - for the most part - have not been handed down to the descendants. In the 1895 census, only 9,607 persons aged five or more spoke indigenous languages. This figure rose to 14,586 in 1910, but dropped to only 305 in the 1930 census, in large part because of the ravages of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), which took the life of one in eight Mexican citizens.

As a matter of fact, Guanajuato's total population fell from an all-time high in the 1910 census (1,081,651 persons) to a Twentieth Century low of 860,364 in the 1921 census. But the 1921 Mexican census gives us a very interesting view of the widespread mestizaje of Guanajuato's modern population. In this census, residents of each state were asked to classify themselves in several categories, including "indígena pura" (pure indigenous), "indígena mezclada con blanca" (indigenous mixed with white), and "blanca" (white). Out of a total district population of 860,364 people, only 25,458 individuals (or 2.96%) claimed to be of pure indigenous background. A much larger number - 828,724, or 96.33% - classified themselves as being mixed, while a mere 4,687 individuals (0.5%) classified themselves as white.

From the latter half of the Twentieth Century into the present century, the population of indigenous speakers has remained fairly small. When the 1970 census was tallied, Guanajuato boasted a mere 2,272 indigenous speakers five years of age and over. The Otomí speakers made up the most significant number (866), followed by the Purépecha (181) and Náhuatl (151). The Chichimeca-Jonaz language, a rare language spoken in only in Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí, was not tallied individually in the 1970 census, but was probably among the 790 persons listed under "otras lenguas Indígenas."

According to the most recent census (2000), the population of persons five years and more who spoke indigenous languages in Guanajuato amounted to only 10,689 individuals, or 0.26% of the total state population. These individuals spoke a wide range of languages, many of which are transplants from other parts of the Mexican Republic. The largest indigenous groups represented in the state were: Chichimeca Jonaz (1,433), Otomí (1,019), Náhuatl (919), Mazahua (626), Purépecha (414), Mixteco (225), and Zapoteco (214).

Today, the Chichimeca-Jonaz language is found only in the states of San Luis Potosí and Guanajuato. Chichimeca Jonaz is classified as a member of the Oto-Manguean language family and is divided into two major dialects: the Pame dialect, which is used in San Luis Potosí, and the Jonaz dialect used in Guanajuato. With a total of 1,433 Chichimeca-Jonaz speakers living in the state of Guanajuato in 2000, it is interesting to note that the great majority - 1,405 persons five years of age or more - actually lived in the municipio of San Luis de la Paz.

All of the other languages spoken in Guanajuato are not well represented. In fact, all of these languages are spoken by many more people living in other Mexican states, some of these states being adjacent to Guanajuato. The Mixteco and Zapoteco are indigenous to the state of Oaxaca, while the other languages have cultural centers in Querétaro, Puebla and Mexico.

The people of Guanajuato are the living representation of their indigenous ancestors. While most of the languages and cultures have disappeared or been absorbed into the central Hispanic culture, the people of Guanajuato have inherited the genetic legacy of the original Indian people. In this respect at least, the indigenous people of pre-Hispanic Guanajuato will endure forever.

Copyright © 2004 by John P. Schmal. All Rights Reserved. Read more articles by John Schmal. Additional articles on The Aztec Empire, the History of Mexico, and Mexican Traditions are available at http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/guanajuato.html

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)